THE PEOPLE WENT WALKING:

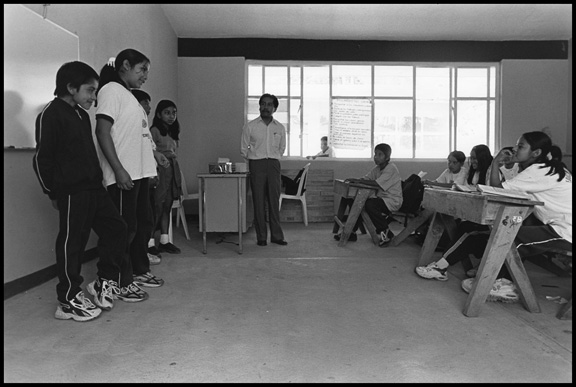

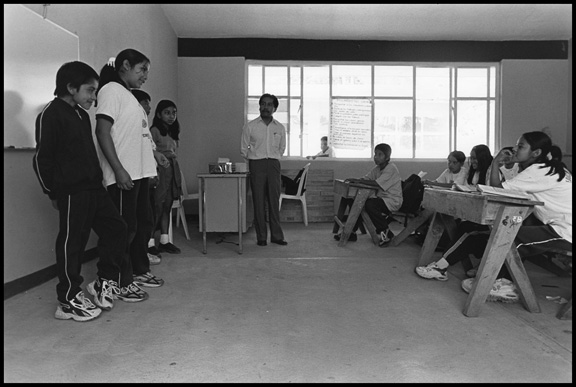

How Rufino Dominguez Revolutionized the Way We Think About Migration Part III By David Bacon Edited by Luis Escala Rabadan Food First | 08.22.2019 https://davidbaconrealitycheck.blogspot.com/2019/08/the-people-went-walking-how-rufino_52.html https://foodfirst.org/publication/the-people-went-walking-how-rufino-dominguez-revolutionized-the-way-we-think-about-migration-part-iii/  Español sigue abajo This publication is the final part of a three part Issue Brief on the life of the radical organizer, Rufino Dominguez. This Issue Brief is part of Food First's Dismantling Racism in the Food System Series. This Issue Brief has also been translated into Spanish. Download the PDF version of this Issue Brief. https://foodfirst.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Rufino-and-FIOB_Part3_english_July11.pdf Part III The FIOB, especially those leaders like Sergio Mendez who were veterans of the strikes and social movements of San Quintin, built chapters in Tijuana, Ensenada and the San Quintin Valley. After Pimentel's expulsion, however, his supporters left, taking many members from the Baja chapters. Then in 2001 Julio Sandoval, a Triqui migrant from Yosoyuxi, Oaxaca, was imprisoned for leading a land occupation in Cañon Buenavista, an hour south of the U.S. border. He spent two years in the Federal prison in Ensenada. His supporters came to the FIOB binational assembly that year for help. After his release he was an active participant in the assemblies in 2005 and 2008. Beatriz Chavez and Julio Cesar Alonzo were the two organizers for CIOAC in San Quintin at the end of the 1990s. Chavez led land occupations also, among Triqui and Mixteco farm workers. Like Sandoval, she was sent to the Ensenada prison. Her health was destroyed by her incarceration, however, and she died not long after her release. Despite the repression, however, the FIOB chapters were reorganized, and when farm workers in San Quintin again went on strike in 2015 the FIOB members were active participants. When the FIOB began to organize in Oaxaca itself, "we began with various productive projects such as the planting of the Chinese pomegranate, the forajero cactus, and strawberries," Rufino explained, "so that families of migrants in the U.S. would have an income to survive." Those efforts grew into five separate offices in the state, and a membership base larger than that in the U.S. in more than 70 towns. In 1999, the Frente entered into an alliance with the PRD and elected Gutierrez Cortez to the state Chamber of Deputies in District 21. "For the first time we beat the caciques," Rufino declared proudly. Following his term in the state Chamber of Deputies, Gutierrez was imprisoned by then-Governor Jose Murat, until a binational campaign, with demonstrations organized by the FIOB at Mexican consulates throughout California, won his release. While the spurious charges against him were quickly dropped, his real crime was insisting on a new path of economic development that would raise rural living standards, and on the political right to organize independently for that goal. "Before my arrest I thought we had a decent justice system," he said. "Then I saw that the people in jail weren't the rich or well educated, but the poor and those who work hard for a living." The Right to Stay Home Gutierrez was a teacher in Tecomaxtlahuaca, a town in the FIOB's main base region in the Mixteca. He and other teachers in the FIOB have been leaders in the state teachers union, Section 22 of the CNTE. In June 2006 a strike by Section 22 led to a months-long uprising, led by the Popular Alliance of People's Organizations (APPO). FIOB leaders, along with other teachers, helped organize the protests. The APPO sought to remove the state's governor, Ulises Ruiz, and make a basic change in development and economic policy. Ezequiel Rosales, who led the union during the strike and insurrection of 2006, later became the FIOB's Oaxaca state coordinator. The uprising was crushed by Federal armed intervention, and dozens of activists were arrested. FIOB leaders were named in arrest warrants as well. According to Leoncio Vasquez, who heads the FIOB office in Fresno, "the lack of human rights itself is a factor contributing to migration from Oaxaca and Mexico, since it closes off our ability to call for any change."  Romualdo Juan Gutierrez Cortez teaching a class in Tecomaxtlahuaca. Photo copyright (c) 2019 by David Bacon. Participating in the APPO reflected the growing demand in the FIOB and other organizations in Oaxaca itself for alternatives to forced migration. The experience of Oaxaca-based activists led to discussions of a new way to look at it. "Migration is a necessity, not a choice," explained Gutierrez. "There is no work here. You can't tell a child to study to be a doctor if there is no work for doctors in Mexico. It is a very daunting task for a Mexican teacher to convince students to get an education and stay in the country. It is disheartening to see a student go through many hardships to get an education here and become a professional, and then later in the United States do manual labor. Sometimes those with an education are working side by side with others who do not even know how to read." He described the bitter feeling of talking to students whose family members were making more money at a blue collar job in the U.S. than he made as the teacher trying to convince them of the value of education. As the FIOB organized its June 2008 binational assembly, dozens of farmers left their fields, and women weavers their looms, to debate the right to stay home instead of being forced to leave Oaxaca to survive. In the community center of Santiago Juxtlahuaca, two hundred Mixtec, Zapotec and Triqui farmers, and a delegation of their relatives working in the U.S., made impassioned speeches, their hot arguments echoing from the cinderblock walls of the cavernous hall. People repeated one phrase over and over: el derecho de no migrar - the right to not migrate. Asserting this right challenges not just the inequality and exploitation facing migrants, but the reasons why people have to migrate to begin with. Indigenous communities were pointing to the need for social change to deal with displacement and the root causes of migration. It was this need that drove the uprising in Oaxaca in 2006.  Rufino talks with former braceros in the palacio del gobierno. Photo copyright (c) 2019 by David Bacon. "We need development that makes migration a choice rather than a necessity - the right to not migrate," said Gaspar Rivera Salgado. "We will find the answer to migration in our communities of origin. To make the right to not migrate concrete, we need to organize the forces in our communities, and combine them with the resources and experiences we've accumulated in 16 years of cross-border organizing. Migration is part of globalization, an aspect of state policies that expel people. Creating an alternative to that requires political power. There's no way to avoid that." Repression of the 2006 uprising by Oaxaca's state government led teachers in Section 22, as well as the FIOB, the PRD and many civil society organizations in Oaxaca, to organize to get rid of the PRI. In the election of 2010, Gabino Cue Monteagudo, the former mayor of Oaxaca city, was elected governor by an unwieldy alliance between the PRD on the left, and the National Action Party on the right. |

[. . .]

LA GENTE SE IBA ANDANDO:

Cómo Rufino Domínguez transformó nuestra manera de pensar acerca de la migración Parte III

Por David Bacon

Traducción por Rosalí Jurado y Alan Llanos Velázquez

Edición: Nancy Utley García y Luis Escala Rabadán

Food FirsT | 08.22.2019

https://foodfirst.org/publication/la-gente-se-iba-andando-como-rufino-dominguez-transformo-nuestra-manera-de-pensar-acerca-de-la-migracion-parte-iii/

Esta publicación es la última de tres Partes sobre Rufino Domínguez, organizador laboral radical de Oaxaca. Pertenece a la serie Desmantelando el Racismo del Sistema Alimentario de Food First. Este artículo originalmente fue escrito en inglés.

Puedes descagar la versión en PDF aquí.

https://foodfirst.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Rufino-and-FIOB_Part3_spanish_July12.pdf

Parte III

El FIOB, y especialmente aquellos líderes como Sergio Méndez, que eran veteranos de las huelgas y movimientos sociales de San Quintín, crearon secciones en Tijuana, Ensenada y el Valle de San Quintín. Sin embargo, después de la expulsión de Pimentel, sus partidarios se fueron, llevándose a muchos miembros de las secciones de Baja California. Luego, en 2001, Julio Sandoval, un migrante triqui de Yosoyuxi, Oaxaca, fue encarcelado por liderar una ocupación de tierras en Cañón Buenavista, a una hora al sur de la frontera con Estados Unidos. Pasó dos años en la prisión federal en Ensenada. Sus seguidores asistieron ese año a la asamblea binacional del FIOB en busca de ayuda. Después de su liberación, participó activamente en las asambleas en 2005 y 2008.

Beatriz Chávez y Julio César Alonzo fueron los dos organizadores de la Central Independiente de Obreros Agrícolas y Campesinos (CIOAC) en San Quintín a fines de la década de 1990. Chávez también lideró las ocupaciones de tierras entre los campesinos triquis y mixtecos. Al igual que Sandoval, fue enviada a la prisión de Ensenada. Sin embargo, su salud se deterioró por el encarcelamiento, y murió poco después de su liberación. Sin embargo, a pesar de la represión, las secciones del FIOB se reorganizaron, y cuando los trabajadores agrícolas en San Quintín volvieron a la huelga en 2015, los miembros del FIOB fueron participantes activos.

Cuando el FIOB comenzó a organizarse en Oaxaca, "comenzamos con varios proyectos productivos, como la siembra de la granada china, el cactus forrajero y las fresas", explicó Rufino, "para que las familias de los migrantes en Estados Unidos tuvieran un ingreso para sobrevivir". Esos esfuerzos se convirtieron en cinco oficinas separadas en el estado y una base de afiliados más grande que la de Estados Unidos en más de 70 ciudades. En 1999, el Frente se alió con el Partido de la Revolución Democrática (PRD) y eligió a Gutiérrez Cortez para la Cámara de Diputados por el Distrito 21. "Por primera vez derrotamos a los caciques", declaró orgullosamente Rufino.

Después de su mandato en la Cámara de Diputados del estado, Gutiérrez fue encarcelado por el entonces gobernador José Murat, hasta que una campaña binacional, con protestas organizadas por el FIOB en los consulados mexicanos en todo California, obtuvo su liberación. Si bien los cargos espurios en su contra se abandonaron rápidamente, su verdadero delito fue insistir en una nueva vía para el desarrollo económico que permitiera incrementar el nivel de vida rural, y en el derecho político a organizarse de manera independiente para el logro de ese objetivo. "Antes de mi arresto, pensé que teníamos un sistema de justicia decoroso", dijo. "Entonces vi que las personas en la cárcel no eran ricos ni tenían buena educación, sino que eran pobres que trabajaban duro para ganarse la vida".

El derecho a quedarse en casa

Gutiérrez fue maestro en Tecomaxtlahuaca, una ciudad en la principal región de influencia del FIOB en la Mixteca. Él y otros en el FIOB han sido líderes en el sindicato de maestros del estado, dentro de la Sección 22 de la Coordinadora Nacional de Trabajadores de la Educación (CNTE). En junio de 2006, una huelga de la Sección 22 provocó una protesta que duró varios meses, liderada por la Asamblea Popular de los Pueblos de Oaxaca (APPO). Los líderes del FIOB, junto con otros profesores, ayudaron a organizar las protestas. La APPO buscó deponer al gobernador del estado, Ulises Ruiz, y establecer un cambio importante en las políticas para el desarrollo y la economía. Ezequiel Rosales, quien dirigió el sindicato durante la huelga y la insurrección de 2006, se convirtió posteriormente en el coordinador del estado de Oaxaca dentro del FIOB. El levantamiento fue aplastado por la intervención armada federal, y docenas de activistas fueron arrestados. También se les giraron órdenes de arresto a los líderes del FIOB. Según Leoncio Vásquez, quien encabeza la oficina del FIOB en Fresno, "la falta de derechos humanos es en sí misma un factor que contribuye a la migración desde Oaxaca y México, ya que nos cierra la posibilidad de demandar cualquier cambio."

Romualdo Juan Gutiérrez Cortez facilitando una clase en Tecomaxtlahuaca. Foto, David Bacon, 2019.

La participación en la APPO reflejó la creciente demanda en el FIOB y en otras organizaciones en Oaxaca de alternativas frente a la migración forzada. La experiencia de activistas basados en Oaxaca condujo a discusiones con una nueva perspectiva.

"La migración es una necesidad, no una elección", explicó Gutiérrez. "Aquí no hay trabajo. No puede decirle a un niño que estudie para ser médico si no hay trabajo para médicos en México. Es una tarea muy desalentadora para un maestro mexicano convencer a los estudiantes para que reciban una educación y permanezcan en el país. Es desalentador ver a un estudiante pasando por muchas dificultades para obtener una educación aquí, convertirse en un profesional, y luego terminar en Estados Unidos haciendo trabajo manual. A veces, quienes tienen una educación trabajan al lado de otros que ni siquiera saben leer". Describió la amarga sensación de hablar con estudiantes cuyos familiares estaban ganando más dinero en un trabajo como obreros en Estados Unidos que el que ganaba el mismo maestro tratando de convencerlos del valor de la educación.

Cuando el FIOB organizó su asamblea binacional en junio de 2008, decenas de campesinos abandonaron sus campos y las mujeres sus telares para debatir sobre el derecho a quedarse en casa, en lugar de verse obligados a abandonar Oaxaca para sobrevivir. En el centro comunitario de Santiago Juxtlahuaca, 200 campesinos mixtecos, zapotecos y triquis, junto con una delegación de sus parientes que trabajaban en Estados Unidos, pronunciaron discursos apasionados, y sus enfáticos argumentos resonaban en las paredes de tabique de la sala cavernosa. La gente repetía la misma frase una y otra vez: el derecho a no migrar.

Afirmar este derecho no sólo desafía la desigualdad y la explotación que enfrentan los migrantes, sino también las razones por las cuales la gente tiene que migrar para empezar. Las comunidades indígenas señalaban la necesidad de un cambio social para enfrentar el desplazamiento y las causas de la migración. Fue esta necesidad la que impulsó el levantamiento en Oaxaca en 2006.

"Necesitamos un desarrollo que haga de la migración una opción más que una necesidad: el derecho a no migrar", dijo Gaspar Rivera-Salgado. "Encontraremos la respuesta a la migración en nuestras comunidades de origen. Para hacer que el derecho a no migrar sea algo concreto, debemos organizar las fuerzas en nuestras comunidades y combinarlas con los recursos y las experiencias que hemos acumulado en 16 años de organización transfronteriza. La migración es parte de la globalización, un aspecto de las políticas estatales que expulsan a las personas. Crear una alternativa a eso requiere poder político. No hay forma de evitar eso."

Rufino habla con los ex braceros en el palacio de gobierno. Foto, David Bacon, 2019.

La represión del levantamiento de 2006 por parte del gobierno del estado de Oaxaca hizo que los maestros de la Sección 22, así como el FIOB, el PRD y muchas organizaciones de la sociedad civil en Oaxaca, se organizaran para deshacerse del PRI. En la elección de 2010, Gabino Cué Monteagudo, ex alcalde de la ciudad de Oaxaca, fue elegido gobernador por una alianza difícil de manejar entre el PRD de la izquierda y el Partido Acción Nacional de la derecha.

Luego de las elecciones, el Gobernador Cué sostuvo una reunión con los líderes del FIOB tanto de Oaxaca como de California, en la cual propusieron medidas para implementar el derecho a no migrar. "Vamos a crear un Oaxaca en el que la migración no sea el destino predestinado de nuestra población rural y urbana", prometió el gobernador. El coordinador binacional del FIOB en ese momento, Gaspar Rivera-Salgado, señaló que "el FIOB ha luchado durante 20 años por los derechos de los migrantes, y ahora queremos luchar por el derecho a no migrar, cambiar las condiciones reales de vida de las personas para que la migración no sea su única alternativa."

[. . .]

Exhibition Schedule

Exhibitions of photographs are scheduled for the following venues and dates:

In the Fields of the North / En los campos del norte

Scheduled exhibitions:

September 1, 2019 - December 22, 2019

Hi-Desert Nature Museum, Yucca Valley

January 5, 2020 - March 1, 2020

Community Memorial Museum of Sutter County, Yuba City

March 15, 2020 - June 21, 2020

Los Altos History Museum, Los Altos

March 21, 2021 - May 23, 2021

Carnegie Arts Center, Turlock

In Washington’s Fields

Scheduled exhibition:

February 5, 2020 - July 15, 2020

Washington State History Museum, Tacoma, WA

More Than a Wall - The Social Movements of the Border

Scheduled exhibition:

August 29,, 2020 - November 29,, 2020

San Francisco Public Library

Deportations

Scheduled exhibition:

April 10, 2020 - May 1, 2020

Uri-Eichen Gallery, Chicago IL

In the Fields of the North / En los Campos del Norte

Photographs and text by David Bacon

University of California Press / Colegio de la Frontera Norte

302 photographs, 450pp, 9”x9”

paperback, $34.95 (in the U.S.)

order the book on the UC Press website:

ucpress.edu/9780520296077

use source code 16M4197 at checkout, receive a 30% discount

En Mexico se puede pedir el libro en el sitio de COLEF:

https://www.colef.mx

Los Angeles Times reviews In the Fields of the North / En los Campos del Norte - clickhere

En los campos del Norte documenta la vida de trabajadores agrícolas en Estados Unidos -

Entrevista con el Instituto Nacional de la Antropologia y Historia

http://www.inah.gob.mx/es/boletines/6863-en-los-campos-del-norte-documenta-la-vida-de-trabajadores-agricolas-en-estados-unidos

Entrevista en la television de UNAM

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xdSaBKZ_k0o

David Bacon comparte su mirada del trabajo agrícola de migrantes mexicanos en el Museo Archivo de la Fotografia

http://www.cultura.cdmx.gob.mx/comunicacion/nota/0038-18

Trabajo agrícola, migración y resistencia cultural: el mosaico de los “Campos del Norte”

Entrevista de David Bacon por Iván Gutiérrez / A los 4 Vientos

http://www.4vientos.net/2017/10/04/trabajo-agricola-migracion-y-resistencia-cultural-el-mosaico-de-los-campos-del-norte/

"Los fotógrafos tomamos partido"

Entrevista por Melina Balcázar Moreno - Milenio.com Laberinto

http://www.milenio.com/cultura/laberinto/david_baconm-fotografia-melina_balcazar-laberinto-milenio_0_959904035.html

Das Leben der Arbeiterschaft auf Ölplattformen des Irak

http://www.nrhz.de/flyer/beitrag.php?id=25973

Die Kunst der Grenze

http://www.nrhz.de/flyer/beitrag.php?id=24304Notruf für "eine andere Welt"

http://www.nrhz.de/flyer/beitrag.php?id=24087

Die Apfel-Pflücker aus dem Yakima-Tal

http://www.nrhz.de/flyer/beitrag.php?id=23990

"Documenting the Farm Worker Rebellion"

"The Radical Resistance to Immigration Enforcement"

Havens Center lectures, University of Wisconsin, click here

San Francisco Commonweallth Club presentation by David Bacon and Jose Padilla, clickhere

EN LOS CAMPOS DEL NORTE: Farm worker photographs on the U.S./Mexico border wall

http://us7.campaign-archive2.com/?u=fc67a76dbb9c31aaee896aff7&id=0644c65ae5&e=dde0321ee7

Entrevista sobre la exhibicion con Alfonso Caraveo (Español)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lJeE1NO4c_M&feature=youtu.beTHE REALITY CHECK - David Bacon blog

http://davidbaconrealitycheck.blogspot.com

Cat Brooks interview on KPFA about In the Fields of the North

https://kpfa.org/player/?audio=263826 - Advance the time to 33:15

Book TV: A presentation of the ideas in The Right to Stay Home at the CUNY Graduate Center

http://booktv.org/Watch/14961/The+Right+to+Stay+Home+How+US+Policy+Drives+Mexican+Migration.aspx

Other Books by David Bacon

The Right to Stay Home: How US Policy Drives Mexican Migration (Beacon Press, 2013)

http://www.beacon.org/productdetails.cfm?PC=2328

Illegal People -- How Globalization Creates Migration and Criminalizes Immigrants (Beacon Press, 2008)

Recipient: C.L.R. James Award, best book of 2007-2008

http://www.beacon.org/Illegal-People-P780.aspx

Communities Without Borders (Cornell University/ILR Press, 2006)

http://www.cornellpress.cornell.edu/book/?GCOI=80140100558350

The Children of NAFTA, Labor Wars on the U.S./Mexico Border (University of California, 2004)

http://www.ucpress.edu/book.php?isbn=9780520244726

En Español:

EL DERECHO A QUEDARSE EN CASA (Critica - Planeta de Libros)

http://www.planetadelibros.com.mx/el-derecho-a-quedarse-en-casa-libro-205607.html

HIJOS DE LIBRE COMERCIA (El Viejo Topo)

http://www.tienda.elviejotopo.com/prestashop/capitalismo/1080-hijos-del-libre-comercio-deslocalizaciones-y-precariedad-9788496356368.html?search_query=david+bacon&results=1

For more articles and images, see http://dbacon.igc.org and http://davidbaconrealitycheck.blogspot.com

and https://www.flickr.com/photos/56646659@N05/albums

Recipient: C.L.R. James Award, best book of 2007-2008

http://www.beacon.org/Illegal-People-P780.aspx

Communities Without Borders (Cornell University/ILR Press, 2006)

http://www.cornellpress.cornell.edu/book/?GCOI=80140100558350

The Children of NAFTA, Labor Wars on the U.S./Mexico Border (University of California, 2004)

http://www.ucpress.edu/book.php?isbn=9780520244726

En Español:

EL DERECHO A QUEDARSE EN CASA (Critica - Planeta de Libros)

http://www.planetadelibros.com.mx/el-derecho-a-quedarse-en-casa-libro-205607.html

HIJOS DE LIBRE COMERCIA (El Viejo Topo)

http://www.tienda.elviejotopo.com/prestashop/capitalismo/1080-hijos-del-libre-comercio-deslocalizaciones-y-precariedad-9788496356368.html?search_query=david+bacon&results=1

For more articles and images, see http://dbacon.igc.org and http://davidbaconrealitycheck.blogspot.com

and https://www.flickr.com/photos/56646659@N05/albums