[Thank you—again!—to those who signed up after the last issue for the modest-priced subscription: it all helps in the goal to make possible a more regular production of this newsletter. You can sign up today…for just five bucks a month, or fifty for the whole year]

Entirely by chance, and within the space of just 20 days just as summer unfolded, three people, with dramatically different moral arcs of life, were tied together. Their un-timed linkage gives us a chance to ponder the power and danger of the national security state, and the way in which the classification of official government documents keeps us all in the dark about what the government does in the name of “national security”. It’s worth a rumination on the three as a lesson of the past, present and, alas, future.

From the war criminal to the simply immoral to the moral, here were the events of those 20 days in May and June:

The War Criminal: Henry Kissinger turned 100 years old on May 27th;

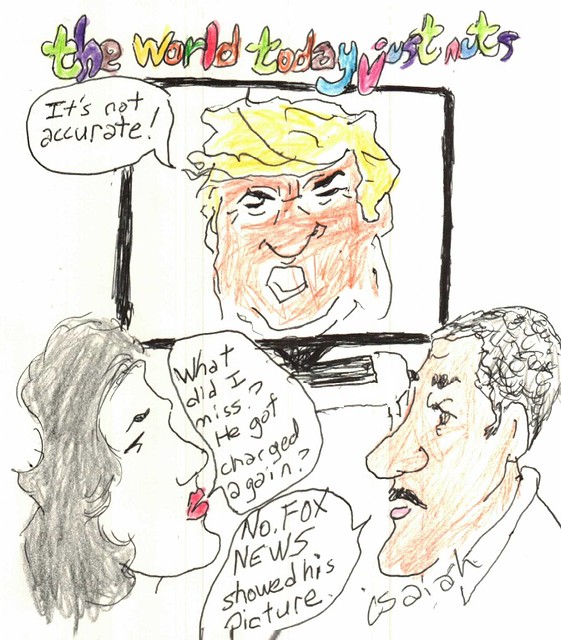

The Immoral: Donald Trump was indicted on June 12th in the Al Capone-like case of the improper storage of classified documents at Mar-a-Lago;

The Moral: Daniel Ellsberg died on June 16th;

Before dragging the three people above into our story today, the big picture of this post is this:

Government secrecy is principally a weapon against its own people, not any explicitly named external enemy. The people who are being bombed in secret by the U.S. (say, Cambodians in the 1970s) or the people being targeted by the CIA for assassination (say, in Iraq, Guatemala, Chile, Indonesia…oh, the list is long) all know what is happening to them—especially in today’s world where nothing can be kept secret if a committed hacker goes to work on a computer network or a privately launched satellite is positioned over virtually any piece of the earth.

It’s the American people who are kept in the dark.

Government secrecy is used to keep information from us, the voters, to keep people from rebelling against or protesting, either at the ballot box or in the streets, in opposition to acts of criminality, war, terror, aggression, violence or just simply hostile diplomacy.

Government secrecy covers up crimes, making a mockery of the slogan “No one is above the law”—because in the U.S., if you are rich and well-connected, you are, in fact, usually above the law or, at worst, the penalty you pay for breaking the law is far, far less than the average person, and that is even more true for people who hold high elected office.

Government secrecy perpetuates the idea of American Exceptionalism, at great cost to the planet. As long as crimes are hidden under layers of secrecy, the bi-partisan cascade of triumphalism and breast-beating messages declaring that this the greatest country in the world drowns out any reality check.

Government secrecy is antithetical to the idea of an informed electorate. When we don’t know what the government does in our name, it is virtually impossible to have a rationale debate about national priorities—say, how to spend wisely the federal budget, our tax dollars—not to mention make decisions at the ballot box.

Government secrecy is perpetuated, daily, by the traditional media. If you are a “national security” journalist—especially the ones who regularly regurgitate Pentagon press releases with the Pentagon seal as a backdrop—you carry a certain mysteriousness and perceived special “access” by invoking your anonymous sources in the national security apparatus, especially if you reference “secret” or “classified documents”. It’s a journalistic aphrodisiac.

Government secrecy exists in a two-tiered system of justice. If you are part of the upper echelons of government, and are part of the elites who have access to “Top Secret” documents, you will never be punished for mishandling classified information in the same fashion as Reality Winner who was prosecuted using the draconian Espionage Act and “was sentenced in 2018 to more than five years on a single count of transmitting national security information — then the longest federal prison sentence imposed for leaks to the news media.” —information she shared because she believed the American public was not being told the truth about alleged Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election.

It’s hard to get attention to the idea of government secrecy. After all, even the concept of “over classification” can make even a committed policy wonk’s eyes glaze over.

On one rare occasion government secrecy and over-classification got a once-over at a House hearing almost seven years ago . The hearing’s conclusions were illuminating, if forgotten in the moment of the day and since [I’ve added the bold]:

Over-classification and excessive secrecy have negative effects on national security and government accountability.

Excessive classification prevents Congress from fully investigating and holding government agencies accountable.

The federal government spent more than $100 billion during the last 10 years on security classification activities, and yet, it is estimated 50 to 90 percent of classified material is not properly labeled.

Federal agencies often mark documents classified and withhold information for decades simply because they contain embarrassing material.

The above conclusions touch on two distinct issues.

There are documents that are given a higher classification than needed—say, marking something “Top Secret” versus just “Secret”, which, then, in theory, limits, at the higher classification level, who can see a piece of information.

The second type of documents are those that are classified, at whatever level, that should not be classified at all—and should be available, free and clear, to any person who wants to see what the government is up to. Many of those documents are often diplomatically embarrassing items—say, a cable from Washington to an embassy giving a frank, negative assessment of a head of state, often an ally. It should not be hidden under the blanket definition of a “national security” secret.

The difference in the level of classification, or what can be declassified, is not an objective decision. The opposite: it’s very subjective.

It’s often a power play (to try to keep a rival in government from having access to a document, which, in turn, gives the possessor of the higher secrecy clearance more leverage and influence) and/or an attempt to conceal from the public eyes embarrassing or politically damaging information, as the House investigation above found.

There is no better example of this then looking at a side-by-side comparison of the Bush and Obama administration versions of the Guantanamo Bay-connected 2004 CIA Inspector General Report on Torture—a report that was ordered by the CIA to look at whether “…certain covert Agency activities at an overseas detention and interrogation site might involve violations of human rights.” Of course, we know now the clear answer—of course, there was torture, blessed by the government.

You don’t have to go through the entire comparison (prepared courtesy of the indispensable National Security Archive) to understand the fundamental point: there was a consistent effort to cover-up and hide internationally illegal, not to mention immoral, actions. The Bush Administration went to great lengths to keep from the public any information about the gross violations of law it had authorized, as you can see by the multiple “Denied in Full” pages. While the Obama Administration gave much more insight into the torture, it still blocked and hid large parts of the history. The secrecy classification of torture, then, and to this day, was done to protect those who ordered the torture from being prosecuted or paying the political price.

Ok, with that very basic, 30,000-foot level description of secrecy and classification, to our three characters of the day.

The War Criminal:

When Kissinger turned 100, I thought, again, of the mind-boggling perversity that he has lived a century of years, far longer than the millions of people who died thanks to his actions in Southwest Asia, Chile and other parts of the globe long before they reached their golden years, including many children.

And the perversity is prolonged at the hands of elites, globally and in both U.S. political parties, who embrace Kissinger, all of whom choose to ignore the blood on his hands and the extensive set of laws he broke that should have earned him a prison cell, not a life of luxury and constant fawning over (from journalists to heads of state to Democratic party nominees).

Anthony Bourdain had it right:

Once you’ve been to Cambodia, you’ll never stop wanting to beat Henry Kissinger to death with your bare hands. You will never again be able to open a newspaper and read about that treacherous, prevaricating, murderous scumbag sitting down for a nice chat with Charlie Rose or attending some black-tie affair for a new glossy magazine without choking. Witness what Henry did in Cambodia—the fruits of his genius for statesmanship—and you will never understand why he’s not sitting in the dock at The Hague next to Milošević.”

That 100th birthday led me to my bookshelf and the masterful book by Seymour Hersh, “The Price of Power: Kissinger In The Nixon White House”. If you have never read it, you should. It is THE indictment of Kissinger—his almost-comical fealty to Richard Nixon, his collusion with the CIA and American corporations in the plot to overthrow Salvador Allende, the democratically-elected president of Chile, which led to countless deaths and a military junta; his bungling of nuclear weapons reduction talks with the then-Soviet Union (which led to four decades of a monstrous arms race); and, of course, his engineering of the murderous Vietnam War for which, if this country actually believed in the rule of law, he would have served a long sentence in prison. It is a portrait of a man without any ethical principles, driven by the sole purpose of his own aggrandizement (to which I reckon many readers, looking at our political class, would say: “He’s in good company”).

It is also a terrific template to understand how political leaders and high-level officials manipulate people inside and outside the government—this is what happens every day, to this day, because people like Kissinger never are held to account. The opposite: for a vast number of people acting in the political realm, the Kissinger lesson is that wealth, access and power are gained through lying and deception.

[Bracing aside: when I went to my bookshelf to grab the book, I was thinking, “wow, this book has got to be at least 20 years old”. Opened up the copyright page: 1983. “Wow, that’s 30 years ago”… pause, beat, better math kicks in…“shit, that’s 40 years ago”. Of course, I’d like you to believe I read this when I was in the first grade…]

To stick to the topic here: Hersh’s book is a road map to understanding how over-classification and obsessive secrecy are used instruments of power. Kissinger used secrecy and classification to amass power within the bureaucracy; it gave him a heightened sense of self-importance—if he held the secrets and you didn’t, he was more important.

Secrecy was his main tool to seize control of the foreign policy apparatus, sidelining and shoving aside then-Secretary of State William P. Rogers (who Kissinger, as Hersh recounts, referred to consistently with the homophobic “fag” slur to his National Security Council aides) from involvement in issues ranging from the Middle East to arms control negotiations with the then-Soviet Union.

Secrecy and classification, though, wasn’t simply confined to bureaucratic manipulations—it was, for example, the instrument used to kill countless Cambodians. As he took office, Nixon, egged on by Kissinger and a young military aide named Alexander (“I’m in control here”) Haig, believed that bombing Cambodia would put pressure on North Vietnam (which had, the Pentagon said, stationed thousands of troops along the Vietnam-Cambodia border), and, by extension, the Soviet Union, to negotiate an end to the war on American terms. Cambodia, it should be mentioned, was a neutral country.

Kissinger insisted that the bombings of Cambodia—code-named “Menu—be kept secret from the Strategic Air Command—the very command-and-control system, as Hersh correctly points out, that oversaw nuclear weapons to prevent unauthorized use. At Kissinger’s direction, the system went like this: B-52 pilots would be briefed before their mission on targets to bomb in South Vietnam but, then, after the “official” briefing would be told that they would be eventually given special instructions once in flight; radar sites would, then, guide the pilots to actually drop their bombs over Cambodia who would return to their bases thinking, and reporting, that their South Vietnam missions had been successful.

Over a 14-month period that ended in April 1970, Hersh writes that Nixon and Kissinger “authorized a total of 3,630 flights over Cambodia; by the Pentagon’s count, the planes dropped 110,000 tons of bombs.” The entire secret campaign against Cambodia was a blatant violation of American law—but its existence was hidden from the public and Congress until the Watergate hearings (as were subsequent secret bombing campaigns in Cambodia, dubbed “Paleo” and “Freedom Deal”). By the way, if you want to get a deeper dive into Kissinger’s Cambodia war crimes, another book on my shelf that I recommend is “Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia” by William Shawcross (who, it must be noted, in recent years has left an indelible mark for spouting despicable anti-Islam views).

As an aside: It’s rarely remembered that an article of impeachment covering Nixon’s illegal bombing of Cambodia was proposed by then-Congressman John Conyers; it was defeated in the Judiciary Committee and never reported out to the full House for a whole set of reasons (that’s a rabbit hole to descend into for another day).

Kissinger’s use of secrecy in arms control would have devastating effects for generations to come. Again, in short: towards the end of 1969 and, then, moving into the 1970s, the U.S. and the Soviet Union engaged in strategic arms limitation talks (SALT) in an effort to curb nuclear weapons. Lurking beneath the talks was the specter of a quantitative and qualitative leap in nukes: the invention and deployment of multiple, independently targeted vehicles, or MIRV, which could carry up to a double-digit warhead payload allowing one missile to suddenly become, in essence, a dozen or more missiles.

To cut to the chase, and grossly synopsize a complicated story, Kissinger, with Nixon’s support, opposed a ban on MIRV development. Kissinger would eventually sideline a group of scientific experts who pushed for a MIRV ban. He kept an iron-hand on the SALT negotiations, bypassing the official SALT delegation, and as a messenger of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (and military-industrial complex) he, essentially, foiled the ban on MIRV.

The key here: this was all done quite secretly. Congress was mostly in the dark, save for a few members who didn’t really know the fine details of the negotiations, and the public had no idea. That secrecy, and classification, had generational consequences: A ban on MIRV, at that time, would have likely kept the number of nuclear weapons far lower, far less threatening (in a military sense) and, as important, would have saved the hundreds of billions of dollars over the ensuing decades that poured into nuclear arms development, from the MX missile system to the goofy Reagan-era “Star Wars” anti-missile system.

Lastly, Hersh argues convincingly (in Chapter 28 “The Plumbers”) that Kissinger knew in advance about the secret plans of the White House to mobilize a “Special Investigations Unit”, better known as “The Plumbers”. Although the popular cultural lore of the Watergate affair that brought down Richard Nixon celebrates the Woodward-Bernstein role and elevates to singular prominence the act of the break-in of Democratic Party national headquarters (the movie “All The Presidents Men” pivots the drama on the break-in), it was the release of the Pentagon Papers that was the initial driving force behind The Plumbers and the cascading set of crimes Richard Nixon committed that would eventually drive him from office—Nixon was enraged and obsessed with Daniel Ellsberg. Kissinger was very much on the same page to target Ellsberg, as much because he feared his past links to Ellsberg would erode his power and singular access to the Oval Office.

Hersh tells us:

The Special Prosecution Force had agreed with the White House early in the Watergate inquiry that all the Nixon-Kissinger meetings were prima facie concerned with national security matters; hence, none of their conversations was ever subpoenaed.

And Hersh concludes:

Only a few Watergate Prosecution Force attorneys fortunate enough to have listened to the White House tapes understood the truth: Kissinger was involved.

So, in Kissinger’s lust for power, we see the full spectrum of what secrecy and classification wrought: illegal wars killing people; assassinations; spying, wiretapping and break-ins to punish political rivals; very bad foreign policy, and the broad perversion of government.

The Immoral:

It is mind-boggling to me that, no matter how many times it happens, year after year, politicians never seem to learn a basic lesson: the cover-up of a crime or misdeed is often worse than the crime or misdeed, or, at the very least, it’s the cover-up that is more easily prosecuted or politically damaging.

Ladies and Gents, I give you Donald Trump.

Look, let’s be clear: I have zero empathy for Donald Trump. He’s an unhinged pig. He’s incompetent, witness his multiple bankruptcies and scams in private business, all the while the fawning media treated him as some business genius. He is only dangerous because he is just an unvarnished, more sleazy, stripped-down manifestation of the cash-hounding sycophants around him and the wingnuts in the Republican Party. He should be in jail based just on his multiple sexual assaults on women. The man was a crook long before he won the White House in 2016.

But, the case of Trump’s possession of classified documents falls well within our discussion today. And calls upon us for a clear-eyed view of the case in spite of what one thinks of the defendant on virtually every other issue.

My reference in the beginning to Trump as Al Capone plays to this truth: Capone never went to prison for his “top-line” crimes of murder and racketeering; he was jailed for tax evasion.

Similarly, in the classified documents indictment, for all of Trumps’s vanity, his fragile ego and his narcissism (the need to show how important he is by whipping out classified documents in a “show-and-tell” moment in front of people not permitted to view the documents), and, perhaps, his desire to pocket the classified documents he could sell for profit or use as leverage, it’s the cover-up (or, as the charge reads, “conspiracy to obstruct justice”), not the underlying crime, that will be his undoing in this case.

Absent ordering people to delete video footage, moving boxes to hide documents or lying to investigators about whether he had kept classified files (the charge in the cover-up is “conspiracy to obstruct justice”) to be consistent, you would have to treat the underlying act—keeping “classified” documents—with the same skepticism one might treat any other individual.

From new reports, the actual content of the documents—quoted from the court documents describing the charges leveled against Trump—include “U.S. nuclear capabilities, U.S. military plans to deal with a foreign attack and details about military operations abroad…which included White House intelligence briefings, communications with foreign leaders, assessments of U.S. and foreign countries' military capabilities and reports on military activities.”

Of course, we don’t know the SPECIFICS of the contents because, naturally, those are secret and classified. So, it’s a bit of a maze, really, which is precisely the problem the secrecy system imposes.

Here is, though, an observation, and it harkens back to the Kissinger-Cambodia bombing: in this day-and-age, no piece of information is unreachable and computers empower unimaginable surveillance and intelligence capabilities for even the smallest countries or private entities; all the information described in the documents Trump possessed is known to the “enemy”, at least, in enough detail to make the “Top Secret” stamp laughable. For example, there is very little unknown to the “enemy” (presumably, principally, China and Russia) about U.S. nuclear capabilities. I recommend you read “The Age of Surveillance Capitalism”—there is no dividing line between military and non-military secrets.

As well, as I wrote earlier, “communications with foreign leaders” are “classified” largely because they could either prove embarrassing or, more important, reveal to the American public what its country is up to globally.

The precedent for treating people who improperly keep classified information goes back years. Joe Biden and Mike Pence both admitted to being in possession of materials with secret classification. Or go back longer to find Sandy Berger, who was Bill Clinton’s top national security aide, who pleaded guilty to taking classified documents but stayed out of prison:

Berger would serve no jail time but instead pay a $10,000 fine, surrender his security clearance for three years and cooperate with investigators.

For trying to overturn the 2020 election, the charges in the state’s case in Georgia, Trump should serve a long sentence in prison. But, if he hadn’t been a fool (okay, admittedly, that’s a high bar), going out of his way to lie, connive and obstruct in the documents case (it should be noted, in a typically ham-handed way), actions for which he is rightly being prosecuted, anything but a mild reproach to the mere fact of keeping documents at Mar-a-Lago should have been met with strong skepticism by anyone challenging the larger landscape of government secrecy and classification.

The Moral Man:

I’m assuming most of my readers know who Daniel Ellsberg was—he was a patriot, in the best sense of the definition of the word: “a person who loves his or her country and is ready to boldly support and defend it”.

Ellsberg risked years of prison time to copy and, then, share with the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and the press the top-secret Pentagon Papers—a 7000-page, 43-volume study of U.S. decision-making in Vietnam from 1945 to 1968, which he had come into possession of through his work at the RAND Corporation. I won’t dive deep into the details of the Pentagon Papers here—there is a mountain of information out there to fill in the blanks. Suffice it to say that the Pentagon Papers were the

Years before he died, Ellsberg published a long rumination called “Secrecy and National Security Whistleblowing”. I think it should be required reading for every politician or government employee right after they are sworn into a job.

I will excerpt here a few segments. The first goes to the heart of the motivation of government secrecy—the desire for power and inclusion in what is essentially a privileged, elite circle:

I am suggesting that in the national security bureaucracy in the executive branch (and now, regrettably, the intelligence committees of Congress as well), the secrecy “oaths” (actually, agreements, conditions of employment or access) have the same psycho-social meaning for participants as the Mafia code of omertà, with the difference that the required “silence to outside authorities” forbids truthful disclosure not to the state or police but to other branches of government and the public.

And:

Thus what is most feared by most prospective secret-tellers—with good reason—is social isolation, ostracism, exile, if they reveal the secrets of the group. If they are found out, they can expect (though not all of them do, beforehand) the loss of friends and relationships, more or less irrevocably, as well as loss of job and career. For someone like myself who has spent a dozen years doing classified work–virtually every colleague I knew during that time had a security clearance, which could be jeopardized by any suggestion that they did not entirely condemn my disclosure of the Pentagon Papers—that means the loss of all your professional friends, semi-permanently. It is as if you were exiled to another country or had emigrated: or as if they had, all of them.

That may seem over-dramatic, but it actually describes the experience rather closely, both in anticipation and in reality. In my own case, after my trial ended in 1973 it was at least fifteen years—roughly until the end of the Cold War—that any former colleague of mine from RAND or the government, with two or three exceptions, would permit themselves to be found even momentarily in a room or a meeting with me. Nor did I hear from any of them ever again, either directly or indirectly. This is a characteristic experience for whistleblowers.

Humans are herd animals. The threat of expulsion from a group on which their well-being and self-regard depends will keep them participating in (or helping to conceal) behavior they would abhor in the absence of that threat. Socialization in the practice of keeping their organization’s secrets gradually blinds them to moral ambiguities or conflicts that might earlier have given them pause. For example, they become less and less mindful that what is being demanded is a loyalty to the institution that is implicitly superior to any other loyalty or obligation whatever, and which overrides altogether the interests of outsiders. Keeping particular secrets that threaten the institution (a lurid instance: widespread child abuse among Catholic clergy) may greatly prejudice the welfare or safety of others, but this is not to be considered in keeping the promise of secrecy or sanctioning violations of it.

And:

There is always a powerful option for those in the executive branch who know, or who come gradually to recognize, that a disastrous course is being chosen or is underway, that the real policy or its costs and dangers are being concealed, and that it is being supported by Congress and the public on the basis of lies and manipulation. That state of awareness is not purely hypothetical. It was true for dozens, perhaps hundreds, of civilian or military officials as America was being lied into escalation in Vietnam in 1964-65 or into invading Iraq in 2001-2003.

Many of them were anguished or distraught, and some made their views known, without effect, to some colleagues or superiors. Some of them, in the case of Iraq, considered resigning or wished later that they had, and a few actually did so, without much notice. Others, like Robert S. McNamara thirty years after his role in Vietnam, wished they had presented their views earlier and more boldly to the President, at the risk of being removed earlier than he actually was.

There was in fact a far more promising path of resistance for all of these dissenters from a hopeless and homicidal policy, one which none of them appear even to have imagined or considered at all. That was not merely to press their case within the executive branch, however strongly, nor to resign in silence: but to use their expertise and access as executive officials or staffers to influence Congress to investigate administration policy and explore alternatives to it, with hearings and subpoena power, and if necessary to use its constitutional power of the purse to force a change in course.

That would have called on them to reveal and expose the executive branch policy and lies to Congress with testimony—their own, and that of other dissenters they could identify to Congressional members and staff—and with documents from their own office safes (or now, computers). It would mean testifying to and working directly with Congress and courts and the press and public associations opposed to the policy. And preferably to do this as an executive official or employee before being fired, and to continue it afterwards.

This is what George Ball or half a dozen others whose dissent to escalation remains less well known (and I and my immediate boss) could and should have done in 1964-65 to avert the Vietnam War. It is what Robert McNamara could and should have done in 1966 or 1967 to end the war after he had come to recognize its hopelessness. It is what Colin Powell or Richard Clarke or a number of their subordinates could and should have done to avert the invasion of Iraq in 2001-03.

And because the above people prized their positions and power, and feared mostly being banished from elite circles, millions of people perished. That is not a hyperbolic figure of humans who lost their lives.

Ellsberg, then, proposes at the end of the essay an alternative system of secrecy [I’ve added some bold parts]:

What would a better secrecy system in a democracy look like? Even to address that question at this time is the very definition of wishful thinking, building castles in the air. But why not? Let’s take a moment to be utopian and consider some features it might have or omit, without asking what we could get from this Congress and this president or the next.

(a) It would, by the premises above, be very much smaller. A system that withheld, more than a few years, only 5% or 1% of what is now guarded in safes would not be a “reformed” system, it would be an entirely different system. It would reflect a strong presumption against secrecy (outside the special categories mentioned in earlier end-notes) beyond a very limited period: automatic declassification for most information after an interval closer to three years than ten.

(b) There would be no legislated equivalent to a broad Official Secrets Act, of the British-type (passed for the first time in October 2000 but vetoed by President Clinton), criminalizing all unauthorized disclosure of classified information. Except for the information already covered by narrow criminal statutes–communications intelligence, nuclear weapons data and identities of clandestine agents–there would be only administrative sanctions for leaks, not criminal penalties. Hence, no grand jury subpoenas for journalists to reveal sources (outside the categories of information covered by existing statutes).v

(c) Legislated whistleblower protection—prohibiting administrative sanctions, let alone prosecution—for all federal national security employees giving classified information non-publicly to any or all members of the Intelligence Committees of Congress (not just the “gang of four”), or to ranking members (at least) of the Armed Services, Foreign Affairs and Budget Committees.

Ideally, the Intelligence Committees themselves should be investigated and reformed, having fatally compromised their “oversight” functions in favor of protecting the intelligence community and keeping its secrets. But at least, there should be immunity from prosecution for informing these others committees of classified evidence of fraud, deception, waste, corruption , illegality or dangerous risk-taking.

(d) Effective whistleblower protection to all federal employees, not vitiated as at present (and past) by appointments of personnel and Inspector Generals who are hostile to whistleblowing.

(e) Immunity from prosecution for revealing what reasonably is judged to be criminal behavior to the press as well as to Congress, prosecutors or courts: this to include information formally covered by communications intelligence clearances (see revelations of illegal NSA warrantless wiretaps and surveillance) or SAP’s (see torture and rendition to torture states and sites).

(f) Resuscitation of the Freedom of Information Act process—as a start, to levels attained in the Clinton administration (reversed under George W. Bush)—with adequate personnel and budget for prompt response, and with newly effective procedures for appealing decisions.

(g) Congressional limitation of the “state secrets privilege,” after thorough investigation of past practices and abuses; skepticism and independent judgment of executive claims of the needs of secrecy by courts.

h) Enforcement of criminal sanctions for lying to Congress by civilian or military officials.

(i) Legislated inclusion in all secrecy agreements, at every level of secrecy: ” I understand that nothing in this agreement obliges me or permits me to give false or misleading testimony to a committee of Congress or a court, or in particular to commit perjury under oath.”

(j) Required briefing of all federal employees, military officers and members of Congress on the operational implications of the Oath of Office they all take, to “support and defend the Constitution of the United States,” with focus on the potential conflicts they may face between this overriding oath and their superiors’ and their own understanding of the requirements of secrecy agreements and obedience to orders.

Frankly, I doubt we will get to a system like the one Ellsberg suggests any time soon. The drumbeat of war is strong. The bi-partisan embrace of the Pentagon and the conjuring up of new Cold War-style enemies (principally, China), I think, only emboldens the current culture of secrecy.

Just be wary. And aware.

Share Working Life Newsletter

Leave a comment

Share