In Iraq, the virus has been surrounded by stigma, driven by religious beliefs, customs and a deep mistrust of the health care system.

Overseeing the “New Wadi al-Salam,” or Valley of Peace, cemetery and helping with the burial procedures are Iraqi Shiite volunteers from the Imam Ali Combat Division. They had been fighting the Islamic State group in Iraq over the past few years, operating under the umbrella group known as the Popular Mobilization Forces.

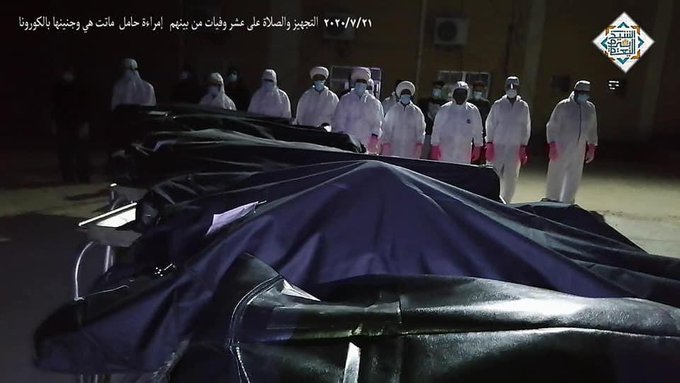

Corpses of the virus victims arrive at night in body bags driven by ambulances and burial procedures take place at daybreak. In the past four months, more than 3,000 bodies have been buried here, said Sarmad Khalaf Ibrahim, an official with the martyrs affairs department of the PMF.

After the coronavirus hit this country of 39 million, doctors began receiving a torrent of abuse from families of COVID-19 patients, escalating the already high scale of violence in Iraq.

The pandemic has further revealed the fragility of Iraq's health system.

Health authorities announced the first coronavirus case in February, in a patient who traveled from Iran to study in Iraq's holy city of Najaf.

It quickly spread across the country.

Inadequate measures from the government, corruption and a lack of medicines added to the struggle of health care workers seeking to deal with the virus.

According to Hawkins, college students have “more power than they know” when it comes to fighting for a better society.

“The study of history will show when you think it’s hopeless, you actually may be winning. In the back of people’s minds you’re winning them over, and they won’t even admit it to you,” he said. “Look at how movements develop, and you will realize you don’t win at first, but you win in the end.”

Hawkins knows a lot about how movements develop. His career in activism began in the Bay Area in the 1960s. There, he was a part of civil rights and anti-war demonstrations. It was during this time Hawkins became focused on the need for a third political party, one which he hoped would understand the issues of the day more than Republicans and Democrats. This thought process culminated in the Green Party, which Hawkins has been involved in since its inception. At the first National Green Gathering in 1987, Hawkins helped chart the party’s way forward.

“My message at that first Green Party meeting was that we can’t build this out of a presidential campaign,” Hawkins said. “We got to build it from the bottom up, organize local groups, get involved in local politics, build a base.”

The Green Party succeeded on that smaller scale for several years before rising to national prominence with the campaigns of Ralph Nader for president in 1996 and 2000. While Nader did not run an active campaign, his name allowed the Green Party to receive a national profile, especially as Democrats blamed his voters for Al Gore’s loss in 2000.

That recognition has continued today, with Green Party candidates garnering votes in every presidential election since 1996. Hawkins understands that Green Party candidates are often considered “spoilers” of the Democratic Party, but he wants to set the record straight, especially during this election season.

“A vote for us is a vote against Trump. It’s not in Trump’s cause. You can vote against Trump by voting for us,” he said. “If you’re a progressive, vote for progressive positions. You vote for Biden, like I like to say, you get lost in the sauce.”

Partially because of this tension between strategy and ideology, Hawkins and the Green Party have been longtime advocates of ranked-choice voting, which they believe would allow citizens to truly vote for who represents them.

“Until the Democrats take that up seriously, don’t tell us we’re spoiling the election,” Hawkins said. “You have the answer; we’ve given it to you for two decades.”