Persistent willful ignorance of necessary knowledge can be deadly. This is true of denial of climate collapse. It is also true of denial of the tools and power of nonviolent action. As evidence and knowledge pile up in each case, denial of the facts looks more and more intentional, reckless, and malevolent, or intentionally, recklessly, and malevolently manufactured by propagandists.

“We need to burn more oil or suffer horribly” is slowly being recognized as a vicious deception, as more and more people come to understand that we need to burn less oil or suffer horribly. “We need to dump more money into war preparations or suffer horribly” is the same type of statement. The notion that a population must be prepared to fight off an invasion and occupation violently or do nothing may someday be understood as on a par with “We need to eat the roasted flesh of livestock or eat nothing.” Some of us grasp that there are other things to eat. Refusing to grasp that there are other ways to resist a military is daily becoming a more irrational act.

The authors of Social Defence define social defense as “nonviolent community resistance to repression and aggression, as an alternative to military forces.” They mean using rallies, strikes, boycotts, and all the thousands of nonviolent tools. Other names for social defense include nonviolent defense, civilian-based defense, and defense by civil resistance. This book provides the case against military defense, and a guide to training for and engaging in social defense. It also provides case studies of times when social defense has been used, and used with some success even without proper training and organization.

Needless to say, roughly half the world’s military spending is by a single country that is under no threat of being occupied but has, on the contrary, attacked and occupied numerous other countries. Yet, ironically, it is a U.S. audience that may most need to gain nonviolent enlightenment, since the propaganda of military defense supports the military spending which generates the distant wars of aggression. For these reasons, it’s important to study how military spending and preparations actually make countries into targets rather than protecting them, and how military propaganda about enemies distracts from the use of armed force to defend anti-democratic rulers from their own people. Not only is the U.S.

arming three-quarters of the world’s dictatorships, but it has armed itself heavily against popular grievances at home.

Johansen and Martin address popular fears of mass slaughter by a foreign invader, by pointing out that most wars never involve any intention of genocide, and that genocides almost always happen within a country and with the support of military forces. Social defense both removes the need for a military and provides people with a means of resisting an attack. While two dozen small nations have abolished their militaries, no nation has replaced its military with, or even created alongside its military, a department of social defense. Nonetheless, people have spontaneously and haphazardly used social defense successfully, demonstrating its enormous potential. Studies of numerous campaigns resisting oppressive governments

have shown nonviolence to be more effective than violence, to be the stronger tool to which one must “resort.” But most such studies do not focus on foreign occupations and coups. Johansen and Martin do.

Social Defence examines German resistance to French occupation in 1923, and Czechoslovakian resistance to Soviet occupation in 1968, making the case that these partial successes could have been more successful with advanced preparation.

When French and Belgian troops occupied the Ruhr in 1923, “The German government called on its citizens to resist the occupation by what was called, at the time, ‘passive resistance,’ namely resistance without physical violence. The key resistance tactic was to refuse to obey orders from the French occupiers. This was costly: thousands who ignored orders were arrested and tried by military tribunals, which handed out heavy fines and prison sentences. There were also protests, boycotts and strikes. The resistance had many facets. The French demanded that owners of coal mines provide them coal and coke. When negotiations broke down, the German negotiators were arrested and court martialled. . . . Civil servants resisted. The German government said they should refuse to obey instructions from the occupiers. Some civil servants were tried for insubordination and given long prison sentences. Others were expelled from the Ruhr; over the course of 1923 nearly 50,000 civil servants were expelled. Transport workers resisted. The French-Belgian occupiers tried to run the railways. Only 400 Germans agreed to work for the new administration, compared to 170,000 who worked in the railways prior to the occupation.”

When the Soviet military invaded Czechoslovakia in 1968, “There were huge demonstrations. There was a one-hour general strike on 22 August. Graffiti, posters and leaflets were used to publicise the resistance. A few individuals sat down in front of tanks. Farmers and shopkeepers refused to provide supplies to the invading troops. Staff at Prague airport cut off central services. The Czechoslovak radio network allowed synchronous broadcasting from many locations across the country. . . The Soviets brought in radio-jamming equipment by train. When this information was broadcast, workers held up the train at a station. Next it was stopped on the main line due to an electricity failure. Finally it was shunted onto a branch line where it was blocked by locomotives at both ends. . . . Announcers told how to avoid detection, harm and arrest, including details of when particular individuals were being hunted. To make the KGB’s job more difficult, citizens removed house numbers and took down or covered over street signs. . . . An effective part of the resistance involved local people talking to the invading soldiers, engaging them in conversation, explaining why they were protesting. Some soldiers had falsely been told there was a capitalist takeover in Czechoslovakia; some of them thought they were in Ukraine or East Germany. . . . For the invading troops, the combination of being met with strong arguments while being refused food and normal social relationships was upsetting, possibly leading some troops to be deliberately inefficient.”

What were the outcomes of these campaigns of social defense avant la lettre?

People nonviolently turned public opinion in Britain, the U.S., and even in Belgium and France, in favor of the occupied Germans. By international agreement, through the

Dawes Commission, 95 years ago this week, the French troops were withdrawn.

Czechoslovakia’s Prague Spring lasted a week. “Dubcek, Svoboda, and other Czechoslovak political leaders were arrested and held in Moscow. Under severe pressure and without communication with the resistance back in Czechoslovakia, they made unwise concessions. They didn’t realise how widespread and resolute the resistance was. The leaders’ concessions deflated the resistance, so its active phase lasted only a week. However, it took another eight months before a puppet government could be installed in Czechoslovakia. The resistance thus failed in its immediate aims. However, it was immensely powerful in its impacts. The use of force against peaceful citizens undermined the credibility of the Soviet Communist Party. At this time, most countries around the world had communist parties, some of them quite strong and most looking to the Soviet party for leadership. The Prague spring changed all this. Many foreign communist parties splintered, with some members quitting or the parties splitting into old guard supporters of the Soviet line and supporters of the reform approach.”

In both cases, nations heavily armed and committed to intervening, and the League of Nations in one case and the United Nations in the other, did nothing — thank goodness!

Social Defence also looks at the use of social defense against coups in Germany 1920, France-Algeria 1961, and the Soviet Union 1991. The lessons learned are widely applicable, including in countries whose governments

refuse to impeach or remove lawless leaders, and in countries whose buffoonish leaders

suspend democratic government.

In Germany in 1920, a coup, led by Wolfgang Kapp, overthrew and exiled the government, but on its way out the government called for a general strike. “Workers shut down everything: electricity, water, restaurants, transport, garbage collection, deliveries. . . . Civilians shunned Kapp’s troops and officials, who could not get anything done. For example, Kapp issued orders, but printers refused to print them. Kapp went to a bank to obtain funds to pay the troops, but bank officials refused to sign cheques. . . . In less than five days, Kapp gave up and fled from the country.”

In Algeria in 1961, four French generals staged a coup. “There was even a possibility of an invasion of France. There were far more French troops in Algeria than in mainland France. There was massive popular opposition to the revolt. After a couple of days of indecisiveness, De Gaulle went on national radio and called for resistance by any possible means. In practice all the resistance was nonviolent. There were huge protests and a general strike. People occupied airstrips to prevent aeroplanes from Algeria landing. The resistance within the French military in Algeria was even more significant. . . . Many of them simply refused to leave their barracks. Another form of noncooperation was deliberate inefficiency, for example losing files and orders, and delaying communications. Many pilots flew their planes out of Algeria and did not return. Others feigned mechanical breakdowns or used their planes to block airfields. The level of noncooperation was so extensive that within a few days the coup collapsed.”

In the Soviet Union in 1991, Gorbachev was arrested at his dacha in Crimea. “Tanks were sent to Moscow, Leningrad and other cities, and plans were made for mass arrests. Strikes and rallies were banned, liberal newspapers were closed and broadcast media were controlled, so most of the country had no news of resistance. . . . The coup leaders seemed to have all the advantages: backing from the armed forces, the KGB (Soviet secret police), the Communist Party and the police, plus the Soviet people’s long acceptance of authority. . . . There was an immediate response, including protests, strikes and messages of opposition. Across the country, including at major industrial complexes, many workers went on strike or just stayed home. Some civilians stood in the path of tanks, whose drivers then took another route. Rallies were held; when the army did not disperse the crowd, this provided a boost for the demonstrators. . . . Within a few days the coup collapsed, almost entirely due to popular noncooperation.”

There are examples beyond those discussed in this book. To quote Stephen Zunes, “During the first Palestinian intifada in the 1980s, much of the subjugated population effectively became self-governing entities through massive noncooperation and the creation of alternative institutions, forcing Israel to allow for the creation of the Palestine Authority and self-governance for most of the urban areas of the West Bank. Nonviolent resistance in the occupied Western Sahara has forced Morocco to offer an autonomy proposal which—while still falling well short of Morocco’s obligation to grant the Sahrawis their right of self-determination—at least acknowledges that the territory is not simply another part of Morocco. In the final years of German occupation of Denmark and Norway during WWII, the Nazis effectively no longer controlled the population. Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia freed themselves from Soviet occupation through nonviolent resistance prior to the USSR’s collapse. In Lebanon, a nation ravaged by war for decades, thirty years of Syrian domination was ended through a large-scale, nonviolent uprising in 2005. And . . . Mariupol became the largest city to be liberated from control by Russian-backed rebels in Ukraine, not by bombings and artillery strikes by the Ukrainian military, but when thousands of unarmed steelworkers marched peacefully into occupied sections of its downtown area and drove out the armed separatists.” I would suggest also the one-time success of the Philippines and the ongoing success of Ecuador in evicting U.S. military bases, and of course the Gandhian example of booting the British out of India.

Yet governments are not investing in social defense, in part — no doubt — because there is no social defense weapons industry from which to make fortunes, and in part — no doubt — because an empowered population can hold a government accountable. So, Johansen and Martin propose another way of developing social defense, namely encouraging social movements to incorporate elements of social defense into their thinking and their campaigning. The authors remark: “The peace movement is the most obvious candidate to promote social defence measures, though it has mainly campaigned against war rather than building capacity for nonviolent action. The environmental movement, by promoting local self-sufficiency in renewable energy production, makes communities less vulnerable to hostile takeover. The labour movement is crucial: when workers have the understanding and skills to take over workplaces and operations, they are ideally placed to resist aggressors. This includes workers in factories, farms and offices. Government employees can play a potent role by refusing to cooperate with occupiers, so administering government operations becomes impossible.”

Social Defence even offers (page 133) an exercise that groups can try in rehearsing nonviolent resistance to occupation.

As a guide to using the tools of nonviolence in social movements, one could hardly do better than to pick up Lisa Fithian’s new book,

Shut It Down. This book includes guides to planning campaigns and to staging all variety of actions in great detail, from how to plaster posters everywhere to how to relate to the police. This is a powerful resource because of the rules it lays out but also because of the examples it includes. The book is as much a personal memoir as a theory of social change, but the latter is its mission throughout.

You have power if you use it, and it’s not found primarily in voting or whining. That’s a central message. And it’s hard not to accept after reading about how much power people have created through nonviolent actions. A sample from the book:

“It’s at the edge of chaos where the deepest changes can emerge. In the dominant culture, the words chaos and crisis often connote violence and destruction, and are used to engender fear. But to me, the edge of chaos is not inherently violent. I have found that violent situations are usually counterproductive, generating fear and demobilizing people. By contrast, nonviolent actions that build strategic crisis can make people feel powerful while exposing the power brokers, convincing them that things have to change.”

Fithian draws conclusions that can guide activism: “There are many ways to organize direct action, but I have found that action is most effective when it takes place within a strong, moderately dense, linked network of participant groups. This is a model of social movement organizing that involves self-organized local groups in a network using working groups, clusters, caucuses, assemblies, or councils as needed. These smaller groups are structures that serve as anchors or hubs in an ever-evolving network.”

These conclusions are based on numerous accounts of specific experiences over the decades and around the world, in the United States, Europe, Egypt, and elsewhere. Fithian was there at the start of Occupy and before the start of Occupy, though she couldn’t know what it would become. She was in Ferguson and at Standing Rock, and draws powerful lessons from each campaign. She got hooked on this work years before with early successes, and she recounts an amazing number of successes over her activist career. One of the earliest successes she mentions was pressuring Governor Michael Dukakis of Massachusetts in 1986 to refuse to send the National Guard to wars in Central America. A sit-in and a little public pressure can go a long way.

Then there was the 1987 shutting down of the CIA. Thousands of people blocked all the entrances to the CIA headquarters for hours as part of the “Pledge of Resistance.” The place re-opened, but a message was sent to the U.S. government, and to participants. The message to the latter was: you have power. Organizers with the Pledge of Resistance “trained tens of thousands of people, organizing them into affinity groups that coordinated with one another in local spokes councils. These processes and structures spread rapidly across the country, with each local network mirroring the other. The Pledge had an explicit structure and tons of flexibility to meet local needs. This is what I now call a hybrid structure, mixing national coordination with local coordinating committees, spokes councils, and affinity groups in an emergency response network. . . . The Reagan administration was never able to invade Nicaragua as they desired, and I believe this was because of the continuing, unrelenting public pressure.”

Around the same time, Fithian worked with Justice for Janitors in Washington, D.C., on a multi-faceted campaign that included blocking bridges. This seemed to work. “Within a few years of our first action at the bridge, 70 percent of the commercial real estate buildings in DC were under a union contract, up from 20 percent in 1987.”

Fithian was also part of the Battle of Seattle, and provides a valuable account of it and its educational and policy successes, as well as the new techniques developed. Fithian was in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina rebuilding and saving schools from destruction. Through these endless and varied struggles, Fithian recounts victories and set backs. A good share of the short comings in terms of results seem to have followed, not unsuccessful nonviolent action, but a failure by activist leaders to use nonviolent action sufficiently. This is a reluctance we simply must overcome.

Fithian embraces diversity and disagreement, humility and openness. She works hard to confront her own white privilege and to put it to good use. But she also offers an empirical, non-theoretical critique of the violent activism often labeled “diversity of tactics.” I recommend sharing her account of her experiences with anyone inclined toward violence. Violence creates problems related to secrecy, an inability to plan ahead, a susceptibility to infiltration and sabotage by police, and of course a problem appealing to the wider public. With regard to infiltration, Fithian concludes:

“In almost every situation over the past twenty years where people have been caught planning a risky or violent action, it turned out that a government infiltrator was in the mix urging them on. This occurred most infamously during the 2008 Republican National Convention protests, when three young white men, in two different situations, were arrested for constructing Molotov cocktails. During their trial it became clear they did not intend to use them, and it came out that an agent provocateur with the FBI had been goading them forward.”

Shut It Down makes a strategic, pragmatic case for the use of many of the tools of social defense. Fithian risks arrest and goes to jail for the sake of social betterment. But she also goes to jail for something else:

“If you’re white or affluent, incarceration might not affect your family at all. This is why I encourage white or otherwise privileged people to make the choice to go to jail for justice. The experience shows you what it’s like to lose your privilege. How easy it is to be criminalized. When they treat you like a criminal, you feel like one. You start questioning yourself, thinking of yourself as a criminal just because they say so. Experiencing this dehumanizing process can make white people understand more about what has been happening to Black and Brown communities for generations. Once you see for yourself how the state enacts violence and robs people of their freedom and dignity, you can never unsee it.”

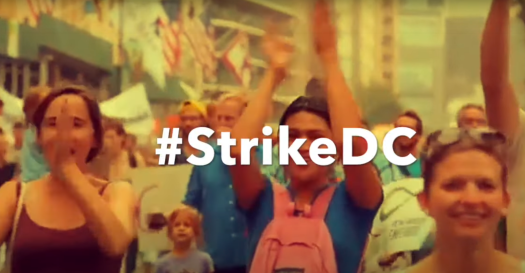

For those looking for an opportunity to put the tools of nonviolence to work, there is

a plan to shut down Washington D.C. for the climate of the earth on September 23rd. The people of DC are of course occupied by a colonial overlord known as the U.S. government, and they will never overcome it violently. Neither is violence a strong enough tool to save the health of this planet. But nonviolence might be.

--

Help support DavidSwanson.org, WarIsACrime.org, and TalkNationRadio.org by clicking here: http://davidswanson.org/donate.Sign up for these emails at https://actionnetwork.org/forms/articles-from-david-swanson.