|

A Pricier Burrito Isn't A Bad Thing

SHORT TAKES: The Rich's Tax Thievery; Global Corporate Tax Rate--You're Joking, Right?; Manchin's Strategy Is Sound And Clear

| Jonathan Tasini | Jun 10 |

LONG TAKE

[PLEASE COMMENT…SHARE THE POST IF YOU THINK IT WILL EDUCATE…SIGN UP A FRIEND AS A SUBSCRIBER!]

I was going to write something about why inflation is not a bad thing—if you aren’t a big bond holder—and the way in which the obsession over inflation and prices says a lot about how screwed up our values are—and, presto, I get the perfect “shill” for the lead-in: Chipotle just announced Wednesday that it was raising its prices about 4 percent to pay for a hike in wages for rank-and-file workers.

That Chipotle is hiking prices will feed, among other nonsense, the fear-mongering you read about inflation, which, in turn, is rhetoric aimed at undermining large government spending proposals. Take note of this as well: the company’s CEO, Brian Niccol, pocketed a cool $38 million in 2020—mostly in a massive bonus that is 1,767 times more than what the average company worker earns in a normal paycheck. Sure, blame price hikes all on rank-and-file workers (eyeroll).

So, let’s wrap our brains around inflation for a moment.

#1: You’ve read this but it’s worth emphasizing and telling your friends—any inflation uptick is almost certainly temporary; it’s caused by (a) price increases after sharp declines because of a year-long, global COVID-19-driven, economic paralysis/collapse and (b) all sorts of factories around the globe having to catch up, because of the COVID freeze, on getting stuff made (semi-conductors, for example) and, in turn, for customers to get the shit they need to do business, either in the form of raw materials or finished goods to sell. To drive this home: Starbucks is running short on basic ingredients to make your beloved whatever coffee. When you have shortages, prices go up—doh!

But, those increases are not, if you will, baked in to the broader economic trends that existed before the pandemic, mainly because the shortages are temporary and, eventually, supply chains will catch up (capitalism abhors a void). Today’s announced consumer price rises, for example, are right in line with short-term, nothing-to-worry-about inflation: increases in food-away-from-home prices; pricier used and new cars (because of shortages in new cars due to semi-conductor shortages); higher airline fares (duh… from no-one-is-flying to people are traveling again, for better or worse).

It’s important that every one of you take the above and spread it around—this is TEMPORARY and in no way should get in the way of big government investment plans, not to mention should in no way pressure the Federal Reserve Board to change its current posture of focusing its policy on getting people jobs.

#2: Inflation doesn’t exist on an island. Meaning: you also have to watch productivity measures. When productivity is higher (meaning, something is being made more efficiently/faster), it essentially reduces the price of a good overall, which, then, tamps down the overall inflation number.

And, presto, productivity has been on the rise since last year for a variety of reasons, including a faster, pandemic-driven introduction of certain automation and technology. A caution: you have to look at last year’s productivity rate, especially in the first half of the year, with a grain of pandemic salt—massive pandemic layoffs happened (=lower costs alas because fewer workers were getting a paycheck) but because there was not the same proportional drop in output that meant a big leap in productivity statistics. But, generally speaking, the productivity trend is pointing up.

A word about productivity: I have consistently hammered home the point that we have all been robbed of the worker productivity gains over the past say 40 years—the federal minimum wage, for example, should be in the range of $22-an-hour, if that rate matched productivity increases. Instead, the fruits of our labor have been essentially pocketed by CEOs and wealthy elites.

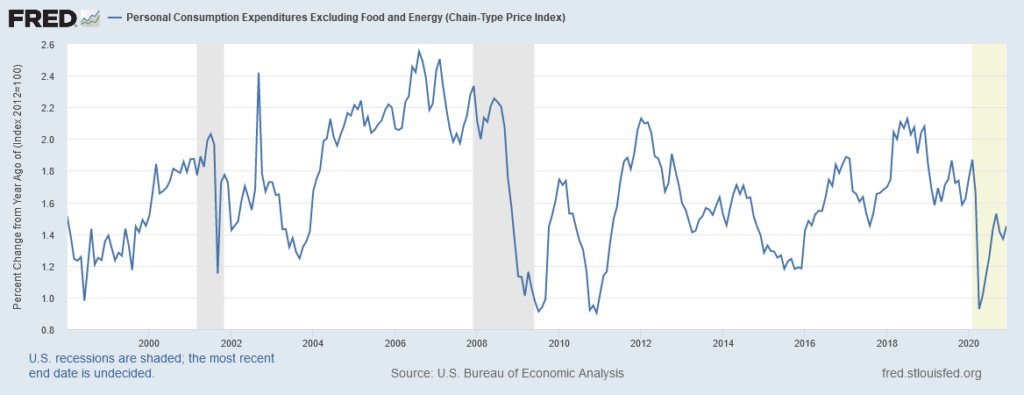

#3: The fear of inflation is truly a relic of the past, fanned by old people and bond holders who lived through the 1970s inflation surge—which was entirely about one thing: oil prices and a geo-political struggle over energy profits. It just isn’t a real problem as you can see from this Fed graph built off of Bureau of Economic Analysis data (the “personal consumption expenditure deflator”) and posted by Dean Baker, senior economist for the Center for Economic and Policy Research:

Dean writes about the inflation levels back to the 1990s reflected above:

As can be seen, the only period where it is above the Fed’s 2.0 percent target (remember, this target is an average) is 2006 and 2007, and even then it is only modestly above 2.0 percent, with no clear upward trend. There is zero evidence of anything like an inflationary spiral in these data. Again, that doesn’t mean it is impossible, just that we haven’t seen anything like it for a long time.

#4: Maybe the most important point about prices is this—a pricier burrito is not a bad thing, morally or even economically. It might mean we may pay a few cents more for the burrito—or, in other instances, for other goods. Morally, in the case of Chipotle, it should mean, if prices are going up Chipotle-style, workers are getting paid more. Economically, it means people have more money in their pockets and have a slightly better chance to not sink into crushing debt (note my emphasis on “slightly better”: until we have national health care and cancel student debt, then, debt will still be a cancer) and might also be able to cope with emergencies (such as a pandemic).

Because the obsession over “lowest price” has been a disaster at every level:

The “lowest price” mantra values human beings as just consumers—which is what capitalism wants to promote.

The “lowest price” strategy has given rise to the greed of the Waltons of Wal-Mart and the Amazon money machine that enriches Jeff Bezos.

The entire “lowest price” agenda also carries with it the other side of human existence: we are workers—and “lower prices” translates into poverty wages.

People shop at Wal-Mart because they are too poor to go anywhere else.

And that cycle just repeats itself, day after day.

It also fuels global poverty because supply chains look to deliver “lower prices” by finding the cheapest (read: slaves) labor possible .

The point is not to fall into the trap that inflation is a worry that should dictate policy. It’s not.

SHORT TAKES

Did you really need a data leak from the Internal Revenue Service to know that the very rich don’t pay taxes? We all knew that. But, still, ProPublica’s “The Secret IRS Files: Trove of Never-Before-Seen Records Reveal How the Wealthiest Avoid Income Tax” is certainly worth the read. Which I did so you don’t have to, with a few nuggets here to offer from the report.

Starting with the icon of the media and political elite, Warren Buffett:

No one among the 25 wealthiest avoided as much tax as Buffett, the grandfatherly centibillionaire. That’s perhaps surprising, given his public stance as an advocate of higher taxes for the rich. According to Forbes, his riches rose $24.3 billion between 2014 and 2018. Over those years, the data shows, Buffett reported paying $23.7 million in taxes.

And:

Buffett has famously held onto his stock in the company he founded, Berkshire Hathaway, the conglomerate that owns Geico, Duracell and significant stakes in American Express and Coca-Cola. That has allowed Buffett to largely avoid transforming his wealth into income. From 2015 through 2018, he reported annual income ranging from $11.6 million to $25 million. That may seem like a lot, but Buffett ranks as roughly the world’s sixth-richest person — he’s worth $110 billion as of Forbes’ estimate in May 2021. At least 14,000 U.S. taxpayers in 2015 reported higher income than him, according to IRS data.

There’s also a second strategy Buffett relies on that minimizes income, and therefore, taxes. Berkshire does not pay a dividend, the sum (a piece of the profits, in theory) that many companies pay each quarter to those who own their stock. Buffett has always argued that it is better to use that money to find investments for Berkshire that will further boost the value of shares held by him and other investors. If Berkshire had offered anywhere close to the average dividend in recent years, Buffett would have received over $1 billion in dividend income and owed hundreds of millions in taxes each year.

Whenever you make a puchase on Amazon (yours truly boycotts the place because anything can be bought locally if you try), think about how you finance Jeff Bezos’ tax dodging:

Consider Bezos’ 2007, one of the years he paid zero in federal income taxes. Amazon’s stock more than doubled. Bezos’ fortune leapt $3.8 billion, according to Forbes, whose wealth estimates are widely cited. How did a person enjoying that sort of wealth explosion end up paying no income tax?

In that year, Bezos, who filed his taxes jointly with his then-wife, MacKenzie Scott, reported a paltry (for him) $46 million in income, largely from interest and dividend payments on outside investments. He was able to offset every penny he earned with losses from side investments and various deductions, like interest expenses on debts and the vague catchall category of “other expenses.”

In 2011, a year in which his wealth held roughly steady at $18 billion, Bezos filed a tax return reporting he lost money — his income that year was more than offset by investment losses. What’s more, because, according to the tax law, he made so little, he even claimed and received a $4,000 tax credit for his children.

His tax avoidance is even more striking if you examine 2006 to 2018, a period for which ProPublica has complete data. Bezos’ wealth increased by $127 billion, according to Forbes, but he reported a total of $6.5 billion in income. The $1.4 billion he paid in personal federal taxes is a massive number — yet it amounts to a 1.1% true tax rate on the rise in his fortune.

Big picture on the 25 richest Americans:

By the end of 2018, the 25 were worth $1.1 trillion.

For comparison, it would take 14.3 million ordinary American wage earners put together to equal that same amount of wealth.

The personal federal tax bill for the top 25 in 2018: $1.9 billion.

The bill for the wage earners: $143 billion.

Speaking of taxes, you might have read that there seems to be a deal among countries at the top of the economic scale—the G7 which includes Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States—to set a minimum global corporate tax rate at 15 percent. In theory, the minimum rate is aimed at forcing corporations to pay at least something on profits earned in a specific country, rather than siphoning of hundreds of billions of dollars into tax havens that are often no more than a post office box number that acts as a registration address.

To which I responded to with a big yawn. 15 percent? Really? That’s it. That’s still lower than the corporate tax rate in the U.S.—21 percent. It’s abundantly clear that this won’t put much of a dent in corporate tax dodging.

And it is suspicious, to put it mildly, that the 15 percent negotiated by the G7 is exactly the number Biden has now offered to set the corporate tax rate at—a drop from the originally proposed 28 percent in his most recent cave to “bi-partisanship”.

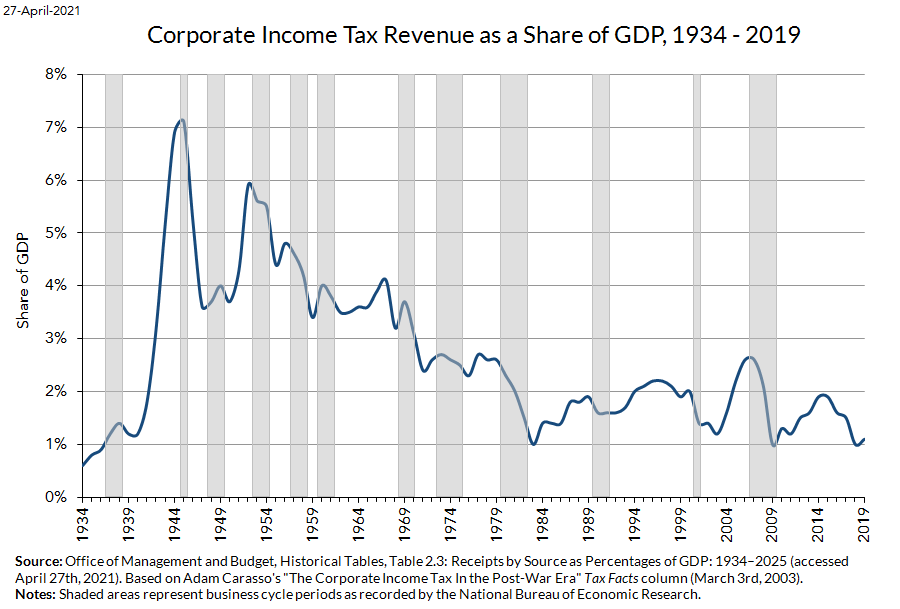

Let me remind everyone what this nice little graph shows—corporate tax revenue has been dropping dramatically over the last 70 years. Which would also explain part of the story of a country falling apart at the seams, and requiring urgent financing of infrastructure:

Oxfam has it right:

It’s about time that some of the world’s most powerful economies force multinational corporations, including tech and pharma giants, to pay their fair share of tax. However, fixing a global minimum corporate tax rate of just 15 percent is far too low. It will do little to end the damaging race to the bottom on corporate tax and curtail the widespread use of tax havens.

It’s absurd for the G7 to claim it is ‘overhauling’ a broken global tax system by setting up a global minimum corporate tax rate that is similar to the soft rates charged by tax havens like Ireland, Switzerland and Singapore. They are setting the bar so low that companies can just step over it.

In a world beset by a pandemic, at a time of such desperate need, the G7 looked at corporate balance sheets bursting at the seams with over-inflated profits ―and immediately looked away. The G7 has failed to help pave the pathway to refilling Covid-wracked government coffers and supporting people all around the world with the promise of better public services and jobs and future opportunities. The G7 had the chance to stand alongside taxpayers. They chose instead to stand alongside tax havens.The Independent Commission for the Reform of International Corporate Taxation has a better take:

apply a higher corporate tax rate to large corporations inoligopolised sectors with excess rates of return;

set a minimum effective corporate tax rate of 25% worldwide to stopbase erosion and profit shifting;

introduce progressive digital services taxes on the economic rentscaptured by multinational firms in this sector;

require publication of country by country reporting for all corporations benefitting from state support;

publish data on offshore wealth to enable all jurisdictions to adopteffective progressive wealth taxes on their residents and to be able to bettermonitor effective income tax rates on highest income taxpayers.

I’m struck by how little, if any, of the discussion around Fifth Columnist Joe Manchin and his “bi-partisan” gambit that is blocking significant legislation gets to the nub of his strategy, which is quite sound and clear: it’s all about his personal re-election prospects and power. You have to understand: even among a class of people who are laser-focused on their own power and careers—Senators!—Manchin stands head-and-shoulders above just about every one of his colleagues. He does not care about civil rights, or infrastructure, or even the people of West Virginia.

And so you heard it here first: Joe Manchin will be a member of the Republican Party a good amount of time before his re-election campaign for 2024.

This is simple math: Trump won West Virginia by almost 40 points in 2020. No statewide Democrat will survive, or win, in 2024 whether Trump runs himself or backs some other clone. Incumbency will not protect Manchin in the current political environment.

So, Manchin’s positions today are completely not about reflecting “the will of the people of West Virginia”, who, by many measure, live in the poorest state in the country and, so, would benefit, disproportionately, from a whole set of the ideas in the proposals being slow-walked by the pointless dance of “bi-partisanship”—child care, family leave, higher unemployment compensation, rebuilding crumbling highways.

Manchin’s positions are 100 percent about being able to use a version of the Ronald Reagan catchy slogan, adapted by various politicians of both parties when convenient, “I left the party because the party left me. I wanted ‘bi-partisanship’, to keep taxes on corporate job creators low, not spend so much money, but the ‘left’ has taken over and blah, blah, blah…” and he will, then, be able to roll out clip after clip of the reams of media he gets parroting his line which he will, then, turn into the justification for his party switch.

This also allows Manchin to switch parties in 2022—especially if the Senate is, again, closely divided and he can deliver the majority to the Republicans, with a promise that he gets to keep his seniority and gets to be chair of a major committee. That’s the ticket to his re-election.

Looked at through that lens of rampant narcissism and increasing one’s personal power and caring not even a little about real people, Manchin’s strategy makes total sense.

If you liked this post from Working Life Newsletter, why not share it?