|

[Consider subscribing… for just five bucks a month, or fifty for the whole year. I’ve set the paywall for free-to-all posts at 3 months, figuring that should be a fair amount of time for readers to dive into some of the ideas, and, then, decide whether keeping this going is valuable. Let me know if you agree.]

I think just about every reader here gets the fraudulent nature of the debate around government debt. Other than it being a manufactured political crisis…

There.

Is.

No.

Debt.

Crisis.

There is no economic reason—none—for this “crisis”. The size of the debt has no relationship—none—to underlying economic issues such as inflation, wages, or unemployment.

That said, I thought I’d just say a few things here as a service, handing out some coherent (hopefully) arguments/ammunition to use with your friends, family, or co-workers.

This is such an old debate. So, an easy start is to go back to 1997 when I wrote a book called “They Get Cake We Get Crumbs: The Real Story Behind Today’s Unfair Economy” (you are welcome to read it for free—it’s intentionally short, and you can read single chapters on their own without having to read the entire book).

Why go all nostalgic about 25 years ago? Because the sad truth is that neither the reality of class warfare, nor the stupidity of the debt debate in political and elite circles, or much of the debate around the economy generally, has changed in 25 years—and, alas, even longer than that. (If you want a more recent take, here’s one from two years ago in this newsletter).

I’ll give you some up-to-date perspective later. But, read the following excerpt from TWENTY FIVE YEARS AGO because it’s all the same damn framework, and this excerpt came out way before social media made things even dumber today:

One of the hottest political debates centers on the perceived dangers of the deficit and the debt. Almost every day, people are told that government deficits are out of control and that future generations will crumble under a terrible debt burden.

First off, these two concepts are often used—by politicians and so-called “expert” talking heads on television—in the wrong way. When we talk about the government spending more money each year than it takes in, that is the deficit. If you add up all the government’s deficits accumulated over a period of time, that is the debt. So, for example, running smaller deficits each year still adds to the overall, long-term debt.

Actually, deficits and a debt are not inherently bad. There are two main questions we need to ask in trying to get through the rhetoric we hear.

First, when the government runs a deficit, what is it spending the money on? Is it going for a long-term public investment (like roads or education)? Or are we, the taxpayers, paying for something else (like a multi-billion dollar bailout of the savings and loan industry or tax cuts for the very wealthy) that does not add to the overall public good? [ADDED NOTE IN 2023: isn’t it just telling how the cancer of tax cuts for the wealthy stands the test of the time as a recurring theme?]

Second, how does the deficit compare to the larger economic picture? Is it a relatively small or large part of overall economic activity? You wouldn’t know it if you listened to the pundits but, in 1995, the U.S. budget deficit was just 2.3 percent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP is one measure used to compare overall economic activity; see Chapter 8). If you looked at the whole world, the U.S. budget deficit compared to the size of the economy is the lowest of the major industrialized countries.

When we hear politicians demanding that Congress balance its checkbook “just like ordinary people have to do everyday,” many of us nod—mistakenly. Indeed, thinking of our own personal conduct is a good way of understanding the larger picture. Working people do spend more than they earn, often times for worthwhile reasons. For example, taking out a loan to send a child to college would be considered a worthy reason—personally and in the eyes of many others—to assume some debt; this would pay off later in, perhaps, your child landing a better job.

On the other hand, running up a huge debt by borrowing money so you can gamble in Las Vegas would not be prudent; it would probably cost less—and be a better long-term investment achieved with a manageable debt—to pay for a counseling program to end a bad gambling habit. Those are all choices we make.

Companies also finance their future with debt—some of it good, some of it bad. Buying new equipment today with borrowed money is a good choice because it will hopefully create new jobs and new revenues that will, in turn, pay off the debt ten years from now. But, taking on huge debt to bankroll a merger for dubious reasons (like raising a company’s stock price so a few top executives can make millions of dollars) can lead to layoffs or bankruptcy, as was too often the case in the 1980s. [ADDED NOTE IN 2023…ummm…has everyone heard, year after year, that tune of “a few top executives can make millions of dollars”?]

The government makes similar choices. The post-WWII boom—which we read in grade school textbooks was the beginning of the American Dream—was financed by a lot of debt. On the other hand, the $5 trillion debt we read about today piled up because of a policy decision in the 1980s—proposed by the Reagan Administration and approved by the Congress—to greatly increase defense spending and cut taxes at the same time. In other words, the policy said “let’s spend a lot more money in this one area without earning more money to cover those costs and, to top it off, let’s also give away truckloads of money we’re supposed to get to pay for our bills.”

So, what is all the commotion about? To some extent, the great concern among voters about the deficits and the debt is a reflection of great anxieties about the economy that have little to do with the deficit and the debt. Except it is easier for us to blame government spending (because we can actually see the people who represent government on television) than wrap our hands around an unfair taxation system (we don’t see the rich people every day who are living it up because they pay practically no taxes) or the freedom of companies to move jobs offshore or cut tens of thousands of jobs.

In the long term—15 years or so—it is certainly not healthy to be building up a large debt if it is unproductive and too burdensome. The question is: how do you reduce the debt?

Let’s go back to the personal experience of a middle-class home. If your family faced a suddenly heavy credit card debt, you would face different options. You could yank your child out of college and toss granny out of a nursing home. Or you could, alternatively, reduce spending on items you can live without (maybe pass on buying a new car, keeping the current car a year or two more). Most people would choose the second option.

So, too, with the government. If we think of society as whole as a family, the question is how are choices balanced. Should the deficit be reduced by cutting spending that benefits many people (such as building roads we all drive on, funding education enriching the minds of the younger generation or keeping the environment safe for entire communities)? Should corporations and the richest among us be asked to pay a fairer share of taxes (see Chapter 3)? Or should we get rid of the deficit by attacking the elderly by cutting Medicare benefits?

Ok, so, now we are in 2023. The debt crisis Groundhog Day.

I’ll just add, as briefly as possible, the 2023 relevant facts.

How does this whole thing work? The good folks at the Economic Policy Institute earlier this year put out a fairly concise, if slightly wonky, explanation:

The U.S. Treasury draws on banking accounts at the Federal Reserve to fund federal governmental activities—remitting paychecks to federal government employees, sending Social Security checks, paying U.S. bondholders, reimbursing medical providers for services covered by Medicare and Medicaid, and so on. These accounts are fed on an ongoing basis by both tax revenues and the proceeds from selling bonds (debt). But since the United States has a statutorily imposed limit of how much outstanding debt is allowed, once this limit is reached on issuing new debt, Treasury can no longer sell bonds and deposit these proceeds. As a result, accounts at the Federal Reserve will dwindle as they are now only fed by incoming taxes, which are insufficient to cover all spending. If Congress does not raise the debt limit, the Biden administration does not enact any work-around, and federal spending is indeed forced to contract to a level that can be financed only by taxes, then the debt limit will “bind” spending.

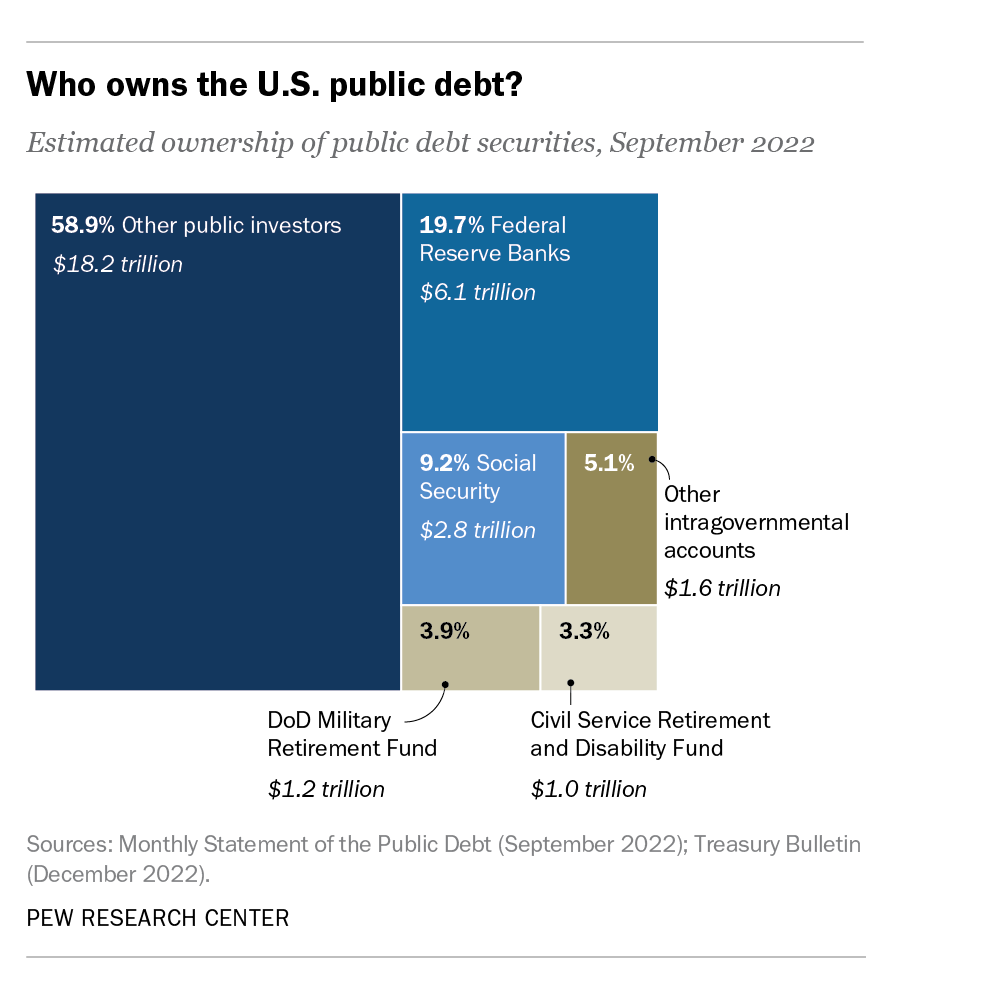

So, what makes up the debt? Courtesy again of a good Pew graph:

Among the things that jump out: just a bit above 16 percent of the debt is Social Security plus two other retirement funds. Then add in the Fed’s debt (which, yes, grew in the pandemic because the Fed increased the amount of Treasury notes it bought and held). So, a hefty 36 percent and change is the entire debt of retirement funds and the Fed’s holdings.

Big Numbers Make Heads Spin: Whoa, the debt is $31 trillion! That is some number—mainly to the transcribers of press releases (formerly known as “journalists”) who don’t read, only trade in gossip, talk to their “sources”, simply repeat nonsense ladled out by “experts” and, to the debt issue, know virtually zero about economics beyond what they might have learned in a college Economics 101 class (that includes Larry Kudlow who is wrong about basically everything—largely because he spouts ideology, not facts).

When you use big numbers, it appears to be impressive, especially to every one of us who usually deal in monetary numbers at amounts to pay for electricity, food, gas and other bills.

But, beyond the “wow” factor, there is rarely any context given to the $31 trillion number. To wit:

Guess what? Today, the size of the U.S. economy—the gross domestic product—is roughly $25.46 trillion, having increased about 9.2 percent in 2022; by 2030 it will likely be close to $34 trillion. So, that gives one some perspective on the ability of the country’s to absorb national debt, in the context of the broader economy.(Aside: there are many problems, mostly societal, relying just on the GDP as a yardstick for how we are doing—but that’s a somewhat separate issue than the long-term debt, one that I’ve raised here and in other places).

The only reason a $31 trillion debt would have any meaning would be if the world/debtors decided (a) to stop using the dollar as the leading trading currency and (b) if debtors decided to collect on the debt. If you believe either of those circumstances are near-term threats (“near-term”=the next 50 years), I have prime swampland in Florida to sell you.

A quick comment on the last couple of years of government spending. It was all worth it—and not enough. I thought that the COVID era relief to people was too small—if the goal was to save peoples’ lives, its smaller size was an outcome of political gamesmanship. If you really wanted to save peoples’ lives, we should have shut down the entire country for 30 days, paid every wage earner who lives paycheck-to-paycheck their full wages, and reimburse actual small businesses for lost revenues. The cost would have been far smaller than the human toll and eventual inflation caused by the global supply chain paralysis from the longer-term spread of the virus. And the Inflation Reduction Act (such a poor, misleading name chosen for cheap political purposes) was a relatively modest gesture to saving the planet.

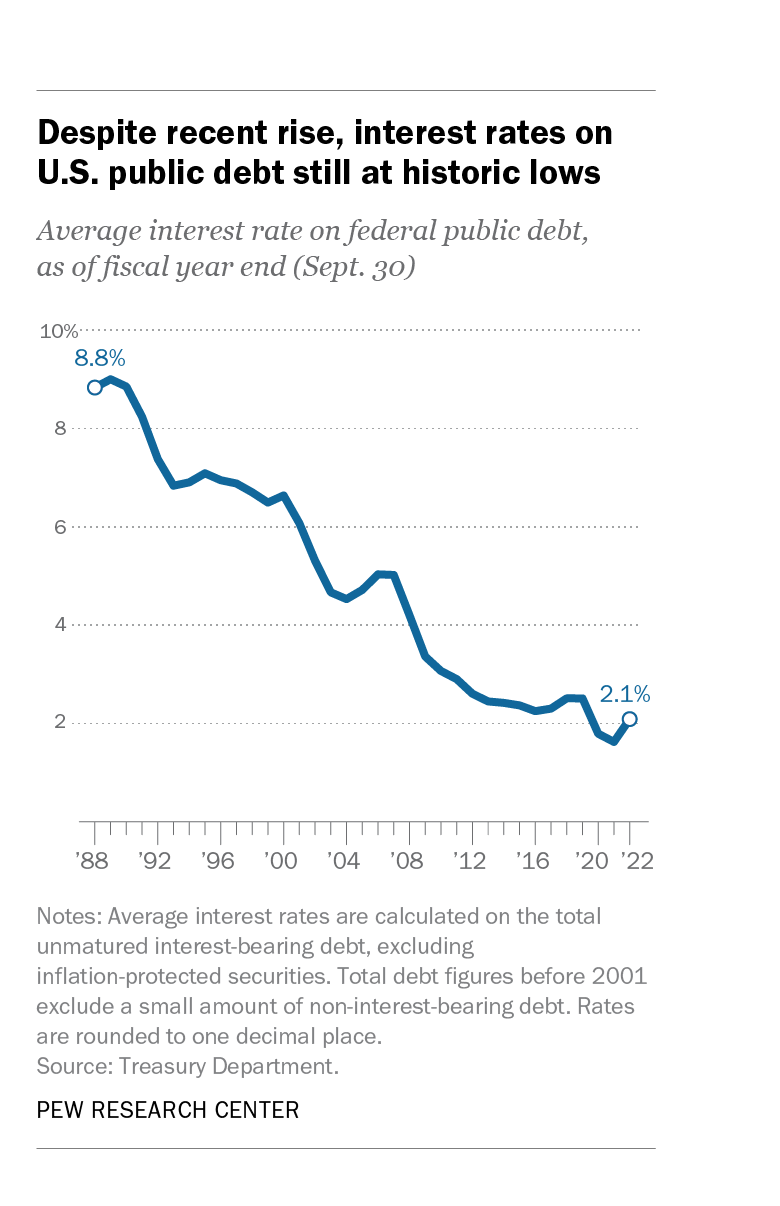

If the debt, accumulated over many years, was truly an issue, interest rates would be a lot higher because the people/investors/countries who keep buying U.S. debt (mainly in the form of U.S. Treasury notes) would be demanding a much bigger premium for the “risk” they saw in not getting their money back. Instead, interest rates have been at historic lows—putting aside the recent rise in interest rates, which had nothing to do with the long term debt of the U.S. Here is another graph from Pew showing how little the current debt costs us compared to 35 years ago:

A Class War Shell Game: the first Pew graph above (“Who owns the U.S. public debt?”) tells a deeper story inside one of the things you likely read in the traditional media that goes roughly like this: one way to avoid debt default is to “reprioritize” or delay payments and just make it up later.

That vanilla explanation is a despicable cover-up. Much of the “other private investors” in the graph are very rich investors and countries (China, for example) who hold U.S. Treasury bonds (partly because those are very safe investments); for them, a slight delay in getting their money (interest payments) is, perhaps, annoying but not particularly consequential.

That isn’t true for seniors waiting for a monthly Social Security check—or for the local supermarket or small business that depends on people spending their retirement money each week for basic necessities. For all those folks, it’s a real hardship to be told “wait a month or more, don’t worry, you’ll be made whole down the road”. They live check-to-check.

Priorities, Priorities: again, this is something you all know. The phony debt limit “crisis” is simply about attacking programs that are deeply popular and using the fog of political war as a cover to do things voters don’t support—principally, cutting Social Security, Medicare, food support for low-income kids.

In other words, the hysteria about the debt really masks two things at play that are about values.

First, what do you fundamentally believe is the role of government?

Second, what do you think is the right way to share wealth, especially in the wealthiest country in the history of human kind (“Wealth” being expressed here as tangible assets, principally money and land).

You could, if you were concerned about the debt, cut it substantially with three steps that would have a lot of benefit:

Significantly raising taxes on the wealthy. Much higher estate taxes, for example. And, heresy of all heresies, tax billionaires out of existence—other than greed and the ideological stupidity of the so-called “free market”, and putting aside the great damage to democracy that such gross wealth concentration encourages, there is no earthly reason, or economic justification to permit such wealth accumulations (and, in fact, a strong argument that such wealth accumulation hampers economic growth) And by significantly raising taxes, I also would cast aside the, ahem, unwise promise by the president, going back to his 2020 campaign, to not raise taxes on individuals earning less than $400,000-a-year; people making, for example, $250,000-a-year should pay higher taxes.

Cut the Pentagon budget at least 50 percent from the Administration’s proposed fiscal 2024 $886 billion bloated monstrosity—a baseline figure that puts the country on track, in short order, for a $1 trillion military budget, not to mention fuels an orgy of weapons manufacturing and a new Cold War.

Making it very easy for workers to organize unions AND raise the federal minimum wage to at least $22-an-hour (which is what it should be if you look at productivity over the past 40 years) because raising peoples’ wages, hello, increases government revenue in the form of taxes—not to mention is good for millions of peoples’ paychecks.

What are your ideas?

You're currently a free subscriber to Working Life Newsletter. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription.